Post Syndicated from Lenka Mareková original https://blog.cloudflare.com/future-proofing-saltstack/

At Cloudflare, we are preparing the Internet and our infrastructure for the arrival of quantum computers. A sufficiently large and stable quantum computer will easily break commonly deployed cryptography such as RSA. Luckily there is a solution: we can swap out the vulnerable algorithms with so-called post-quantum algorithms that are believed to be secure even against quantum computers. For a particular system, this means that we first need to figure out which cryptography is used, for what purpose, and under which (performance) constraints. Most systems use the TLS protocol in a standard way, and there a post-quantum upgrade is routine. However, some systems such as SaltStack, the focus of this blog post, are more interesting. This blog post chronicles our path of making SaltStack quantum-secure, so welcome to this adventure: this secret extra post-quantum blog post!

SaltStack, or simply Salt, is an open-source infrastructure management tool used by many organizations. At Cloudflare, we rely on Salt for provisioning and automation, and it has allowed us to grow our infrastructure quickly.

Salt uses a bespoke cryptographic protocol to secure its communication. Thus, the first step to a post-quantum Salt was to examine what the protocol was actually doing. In the process we discovered a number of security vulnerabilities (CVE-2022-22934, CVE-2022-22935, CVE-2022-22936). This blogpost chronicles the investigation, our findings, and how we are helping secure Salt now and in the Quantum future.

Cryptography in Salt

Let’s start with a high-level overview of Salt.

The main agents in a Salt system are servers and clients (referred to as masters and minions in the Salt documentation). A server is the central control point for a number of clients, which can be in the tens of thousands: it can issue a command to the entire fleet, provision client machines with different characteristics, collect reports on jobs running on each machine, and much more. Depending on the architecture, there can be multiple servers managing the same fleet of clients. This is what makes Salt great, as it helps the management of complex infrastructure.

By default, the communication between a server and a client happens over ZeroMQ on top of TCP though there is an experimental option to switch to a custom transport directly on TCP. The cryptographic protocol is largely the same for both transports. The experimental TCP transport has an option to enable TLS which does not replace the custom protocol but wraps it in server-authenticated TLS. More about that later on.

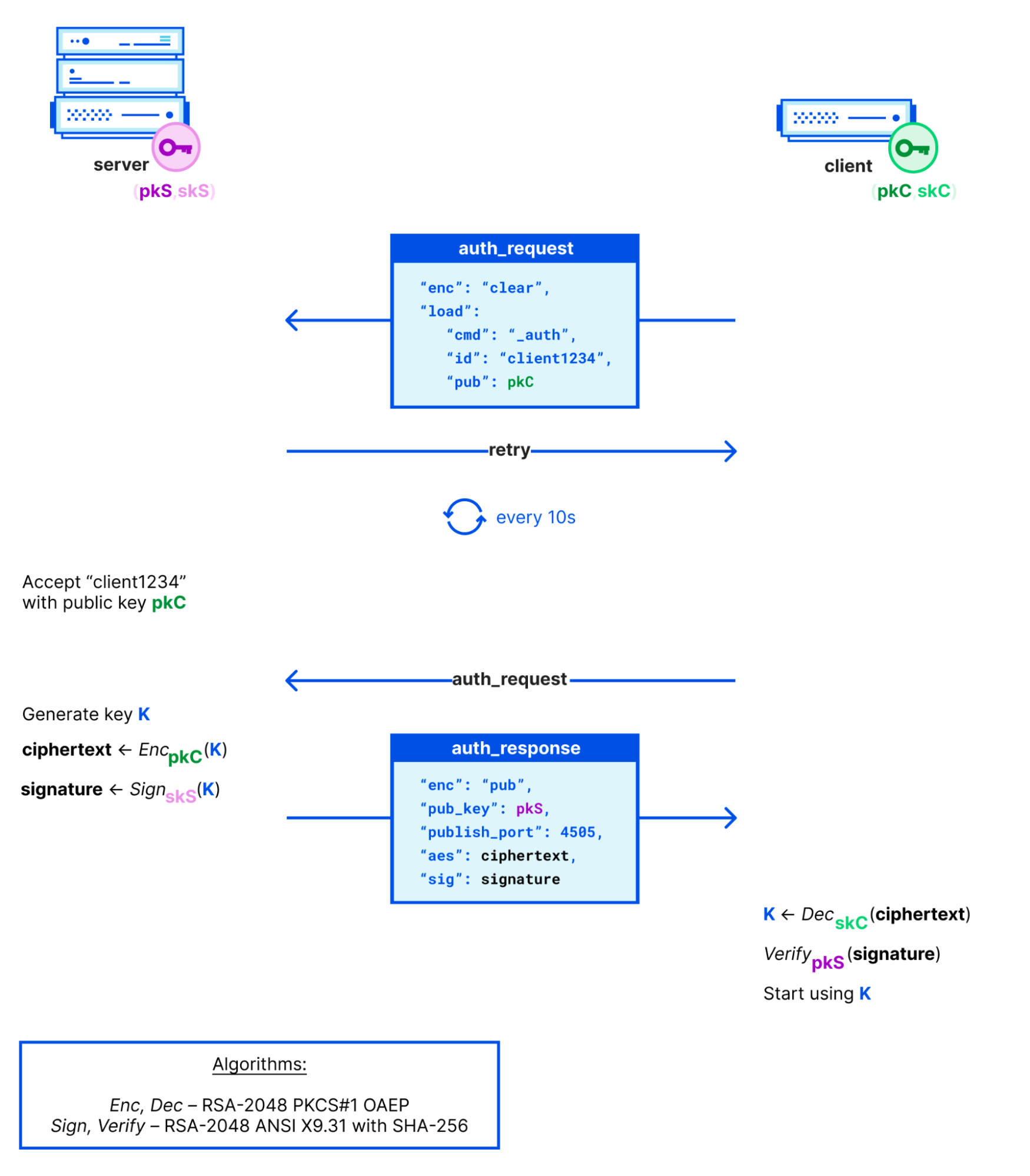

The custom protocol relies on a setup phase in which each server and each client has its own long-term RSA-2048 keypair. On the surface similar to TLS, Salt defines a handshake, or key exchange protocol, that generates a shared secret, and a record protocol which uses this secret with symmetric encryption (the symmetric channel).

Key exchange protocol

In its basic form, the key exchange (or handshake) protocol is an RSA key exchange in which the server chooses the secret and encrypts it to the client’s public key. The exact form of the protocol then depends on whether either party already knows the other party’s long-term public key, since certificates (like in TLS) are not used. By default, clients trust the server’s public key on first use, and servers only trust the client’s public key after it has been accepted by an out-of-band mechanism. The shared secret is shared among the entire fleet of clients, so it is not specific to a particular server and client pair. This allows the server to encrypt a broadcast message only once. We will come back to this performance trade-off later on.

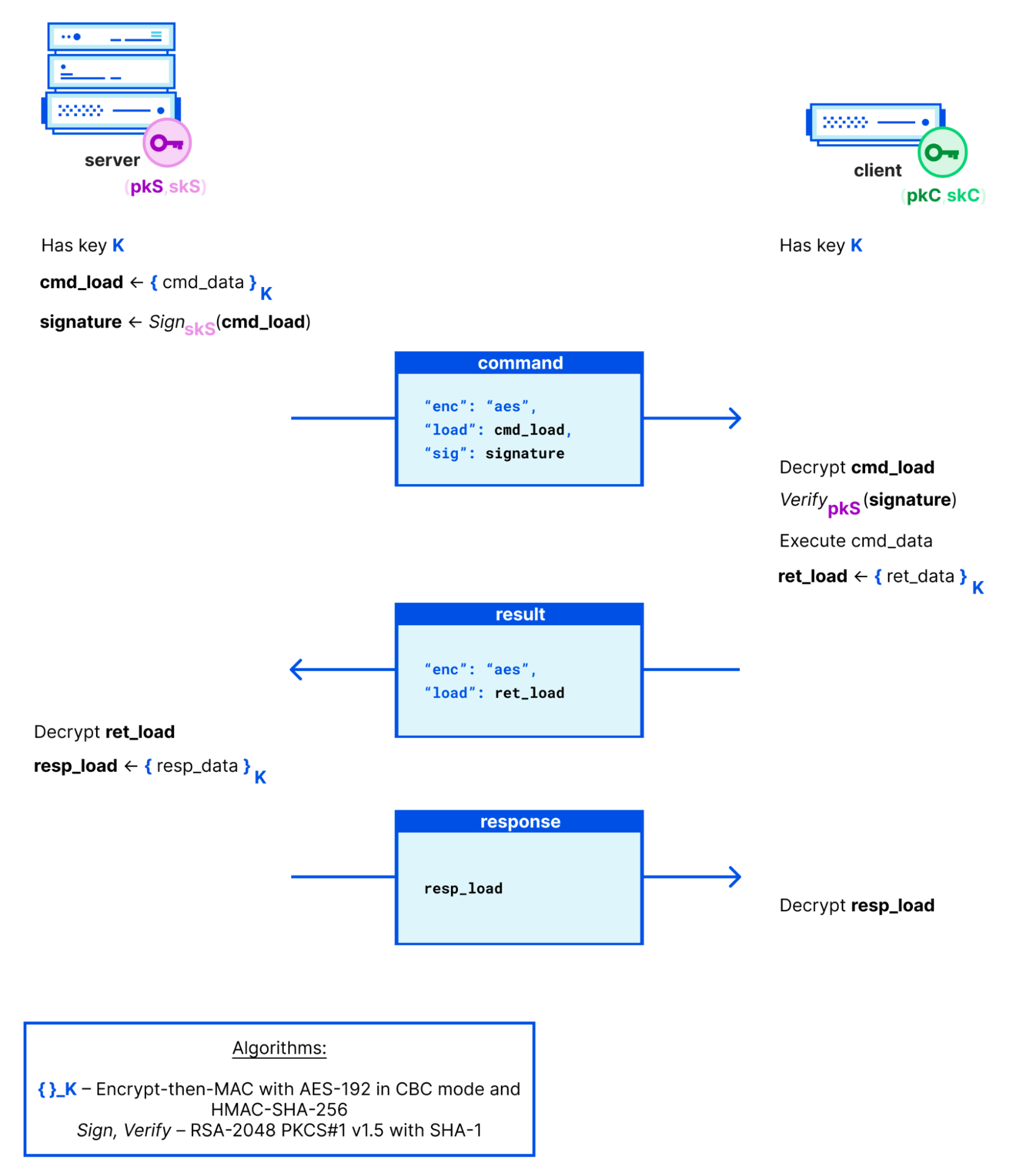

Symmetric channel

The shared secret is used as the key for encryption. Most of the messages between a server and a client are secured in an Encrypt-then-MAC fashion, with AES-192 in CBC mode with SHA-256 for HMAC. For certain more sensitive messages, variations on this protocol are used to add more security. For example, commands are signed using the server’s long-term secret key, and “pillar data” (deemed more sensitive) is encrypted only to a particular client using a freshly generated secret key.

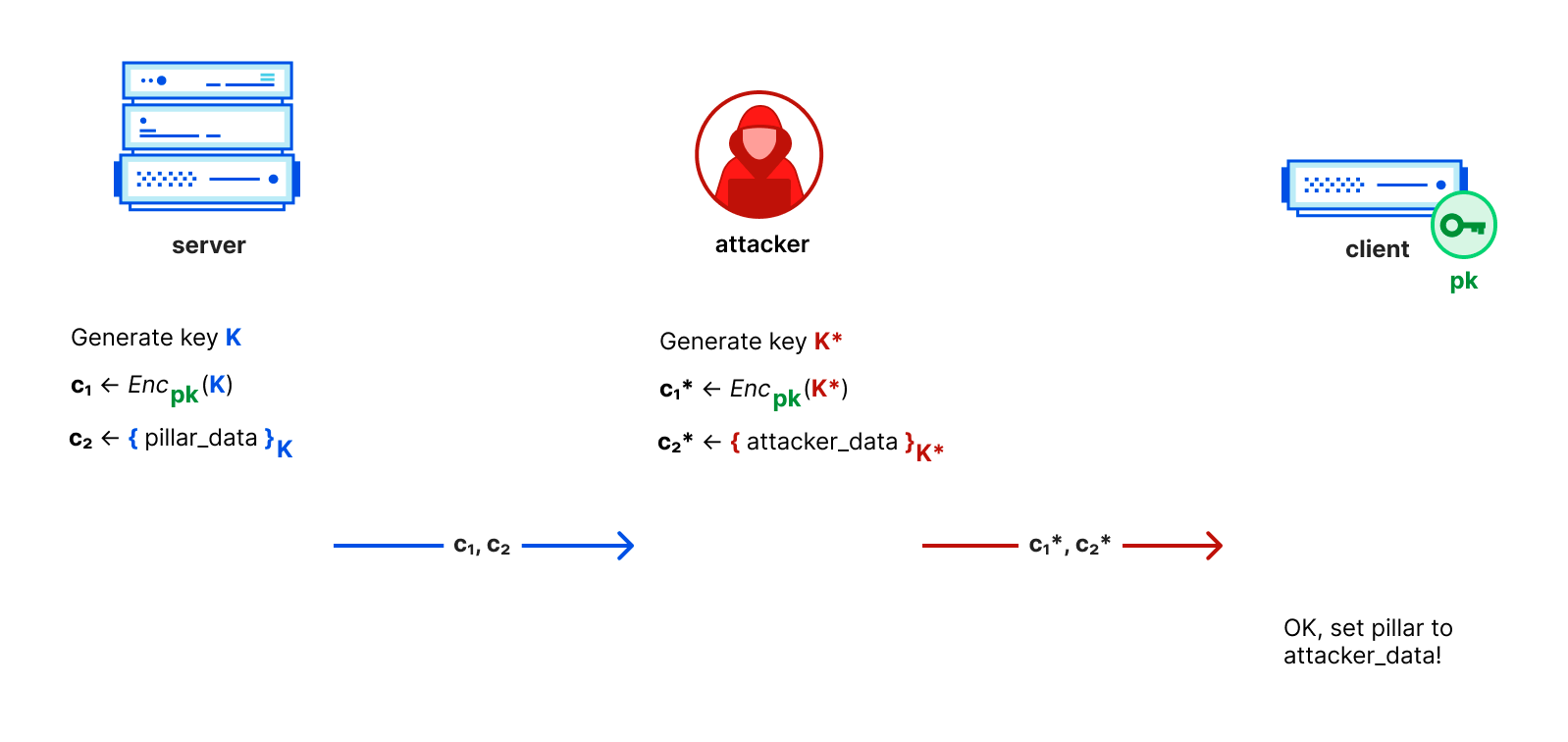

Security vulnerabilities

We found that the protocol variation used for pillar messages contains a flaw. As shown in the diagram below, a monster-in-the-middle attacker (MitM) that sits between a server and a client can substitute arbitrary “pillar data” to the client. It needs to know the client’s public key, but that is easy to find since clients broadcast it as part of their key exchange request. The initial key exchange can be observed, or one could be triggered on-demand using a specially crafted message. This MitM was possible because neither the newly generated key nor the actual payload were authenticated as coming from the server. This matters because “pillar data” can include anything from specifying packages to be installed to credentials and cryptographic keys. Thus, it is possible that this flaw could allow an attacker to gain access to the vulnerable client machine.

We reported the issue to Salt November 5, 2021, which assigned CVE-2022-22934 to it. Earlier this week, on March 28, 2022, Salt released a patch that adds a signature of the server on the pillar message to prevent the attack.

There were several other smaller issues we found. Messages could be replayed to the same or a different client. This could allow a file intended for one client, to be served to a different one, perhaps aiding lateral movement. This is CVE-2022-22936 and has been patched by adding the name of the addressed client, a nonce and a signature to messages.

Finally, there were some messages which could be manipulated to cause the client to crash. This is CVE-2022-22935 and was patched similarly by adding the addressee, nonce and signature.

If you are running Salt, please update as soon as possible to either 3002.8, 3003.4 or 3004.1.

Moving forward

These patches add signatures to almost every single message. The decision to have a single shared secret was a performance trade-off: only a single encryption is required to broadcast a message. As signatures are computationally much more expensive than symmetric encryption, this trade-off didn’t work out that well. It’s better to switch to a separate shared key per client, so that we don’t need to add a signature on every separate message. In effect, we are creating a single long-lived mutually-authenticated channel per client. But then we are getting very close to what mutually authenticated TLS (mTLS) can provide. What would that look like? Hold that thought for a moment: we will return to it below.

We got sidetracked from our original question: what does this all mean for making Salt post-quantum secure? One thing to take away about post-quantum cryptography today is that signatures are much larger: Dilithium2, for instance, weighs in at 2.4 kB compared to 256 bytes for an RSA-2048 signature. So ironically, patching these vulnerabilities has made our job more difficult as there are many more signatures. Thus, also for our post-quantum goal, mTLS seems very attractive. Not the least because there are post-quantum TLS stacks ready to go.

Finally, as the security properties of mTLS are well understood, it will be much easier to add new messages and functionality to Salt’s protocol. With the current complex protocol, any change is much harder to judge with confidence.

An mTLS-based transport

So what would such an mTLS-based protocol for Salt look like? Clients would pin the server certificate and the server would pin the client certificates. Thus, we wouldn’t have any traditional public key infrastructure (PKI). This matches up nicely with how Salt deals with keys currently. This allows clients to establish long-lived connections with their server and be sure that all data exchanged between them is confidential, mutually authenticated and has forward secrecy. This mitigates replays, swapping of messages, reflection attacks or subtle denial of service pathways for free.

We tested this idea by implementing a third transport using WebSocket over mTLS (WSS). As mentioned before, Salt already offers an option to use TLS with the TCP transport, but it doesn’t authenticate clients and creates a new TCP connection for every client request which leads to a multitude of unnecessary TLS handshakes. Internally, Salt has been architected to work with new connections for each request, so our proof of concept required some laborious retooling.

Our findings show promise that there would be no significant losses and potentially some improvements when it comes to performance at scale. In our preliminary experiments with a single server handling a thousand clients, there was no difference in several metrics compared to the default ZeroMQ transport. Resource-intensive operations such as the fetching of pillar and state data resulted, in our experiment, in lower CPU usage in the mTLS transport. Enabling long-lived connections reduced the amount of data transmitted between the clients and the server, in some cases, significantly so.

We have shared our preliminary results with Salt, and we are working together to add an mTLS-based transport upstream. Stay tuned!

Conclusion

We had a look at how to make Salt post-quantum secure. While doing so, we found and helped fix several issues. We see a clear path forward to a future post-quantum Salt based on mTLS. Salt is but one system: we will continue our work, checking system-by-system, collaborating with vendors to bring post-quantum into the present.

With thanks to Bas and Sofía for their help on the project.