Post Syndicated from Thibault Meunier http://blog.cloudflare.com/author/thibault/ original https://blog.cloudflare.com/privacy-pass-standard

Enabling anonymous access to the web with privacy-preserving cryptography

The challenge of telling humans and bots apart is almost as old as the web itself. From online ticket vendors to dating apps, to ecommerce and finance — there are many legitimate reasons why you’d want to know if it’s a person or a machine knocking on the front door of your website.

Unfortunately, the tools for the web have traditionally been clunky and sometimes involved a bad user experience. None more so than the CAPTCHA — an irksome solution that humanity wastes a staggering amount of time on. A more subtle but intrusive approach is IP tracking, which uses IP addresses to identify and take action on suspicious traffic, but that too can come with unforeseen consequences.

And yet, the problem of distinguishing legitimate human requests from automated bots remains as vital as ever. This is why for years Cloudflare has invested in the Privacy Pass protocol — a novel approach to establishing a user’s identity by relying on cryptography, rather than crude puzzles — all while providing a streamlined, privacy-preserving, and often frictionless experience to end users.

Cloudflare began supporting Privacy Pass in 2017, with the release of browser extensions for Chrome and Firefox. Web admins with their sites on Cloudflare would have Privacy Pass enabled in the Cloudflare Dash; users who installed the extension in their browsers would see fewer CAPTCHAs on websites they visited that had Privacy Pass enabled.

Since then, Cloudflare stopped issuing CAPTCHAs, and Privacy Pass has come a long way. Apple uses a version of Privacy Pass for its Private Access Tokens system which works in tandem with a device’s secure enclave to attest to a user’s humanity. And Cloudflare uses Privacy Pass as an important signal in our Web Application Firewall and Bot Management products — which means millions of websites natively offer Privacy Pass.

In this post, we explore the latest changes to Privacy Pass protocol. We are also excited to introduce a public implementation of the latest IETF draft of the Privacy Pass protocol — including a set of open-source templates that can be used to implement Privacy Pass Origins, Issuers, and Attesters. These are based on Cloudflare Workers, and are the easiest way to get started with a new deployment of Privacy Pass.

To complement the updated implementations, we are releasing a new version of our Privacy Pass browser extensions (Firefox, Chrome), which are rolling out with the name: Silk – Privacy Pass Client. Users of these extensions can expect to see fewer bot-checks around the web, and will be contributing to research about privacy preserving signals via a set of trusted attesters, which can be configured in the extension’s settings panel.

Finally, we will discuss how Privacy Pass can be used for an array of scenarios beyond differentiating bot from human traffic.

Notice to our users

- If you use the Privacy Pass API that controls Privacy Pass configuration on Cloudflare, you can remove these calls. This API is no longer needed since Privacy Pass is now included by default in our Challenge Platform. Out of an abundance of caution for our customers, we are doing a four-month deprecation notice.

- If you have the Privacy Pass extension installed, it should automatically update to Silk – Privacy Pass Client (Firefox, Chrome) over the next few days. We have renamed it to keep the distinction clear between the protocol itself and a client of the protocol.

Brief history

In the last decade, we’ve seen the rise of protocols with privacy at their core, including Oblivious HTTP (OHTTP), Distributed aggregation protocol (DAP), and MASQUE. These protocols improve privacy when browsing and interacting with services online. By protecting users’ privacy, these protocols also ask origins and website owners to revise their expectations around the data they can glean from user traffic. This might lead them to reconsider existing assumptions and mitigations around suspicious traffic, such as IP filtering, which often has unintended consequences.

In 2017, Cloudflare announced support for Privacy Pass. At launch, this meant improving content accessibility for web users who would see a lot of interstitial pages (such as CAPTCHAs) when browsing websites protected by Cloudflare. Privacy Pass tokens provide a signal about the user’s capabilities to website owners while protecting their privacy by ensuring each token redemption is unlinkable to its issuance context. Since then, the technology has turned into a fully fledged protocol used by millions thanks to academic and industry effort. The existing browser extension accounts for hundreds of thousands of downloads. During the same time, Cloudflare has dramatically evolved the way it allows customers to challenge their visitors, being more flexible about the signals it receives, and moving away from CAPTCHA as a binary legitimacy signal.

Deployments of this research have led to a broadening of use cases, opening the door to different kinds of attestation. An attestation is a cryptographically-signed data point supporting facts. This can include a signed token indicating that the user has successfully solved a CAPTCHA, having a user’s hardware attest it’s untampered, or a piece of data that an attester can verify against another data source.

For example, in 2022, Apple hardware devices began to offer Privacy Pass tokens to websites who wanted to reduce how often they show CAPTCHAs, by using the hardware itself as an attestation factor. Before showing images of buses and fire hydrants to users, CAPTCHA providers can request a Private Access Token (PAT). This native support does not require installing extensions, or any user action to benefit from a smoother and more private web browsing experience.

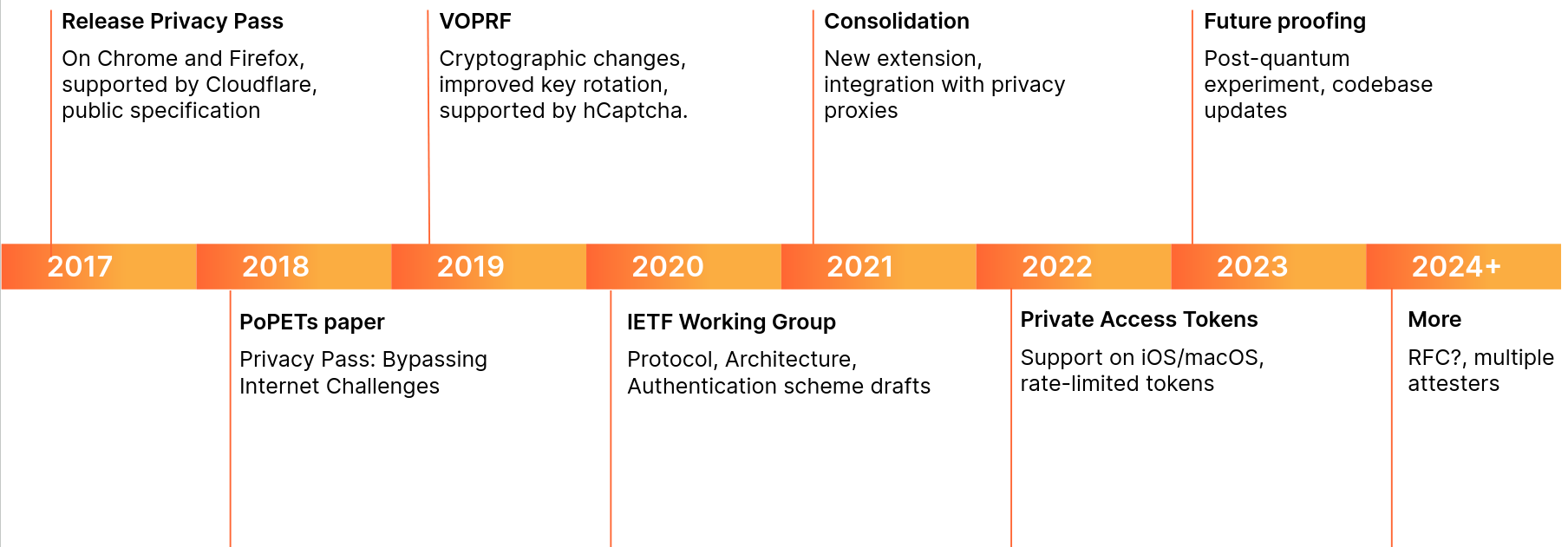

Below is a brief overview of changes to the protocol we participated in:

The timeline presents cryptographic changes, community inputs, and industry collaborations. These changes helped shape better standards for the web, such as VOPRF (RFC 9497), or RSA Blind Signatures (RFC 9474). In the next sections, we dive in the Privacy Pass protocol to understand its ins and outs.

Anonymous credentials in real life

Before explaining the protocol in more depth, let’s use an analogy. You are at a music festival. You bought your ticket online with a student discount. When you arrive at the gates, an agent scans your ticket, checks your student status, and gives you a yellow wristband and two drink tickets.

During the festival, you go in and out by showing your wristband. When a friend asks you to grab a drink, you pay with your tickets. One for your drink and one for your friend. You give your tickets to the bartender, they check the tickets, and give you a drink. The characteristics that make this interaction private is that the drinks tickets cannot be traced back to you or your payment method, but they can be verified as having been unused and valid for purchase of a drink.

In the web use case, the Internet is a festival. When you arrive at the gates of a website, an agent scans your request, and gives you a session cookie as well as two Privacy Pass tokens. They could have given you just one token, or more than two, but in our example ‘two tokens’ is the given website’s policy. You can use these tokens to attest your humanity, to authenticate on certain websites, or even to confirm the legitimacy of your hardware.

Now, you might wonder if this is a technique we have been using for years, why do we need fancy cryptography and standardization efforts? Well, unlike at a real-world music festival where most people don’t carry around photocopiers, on the Internet it is pretty easy to copy tokens. For instance, how do we stop people using a token twice? We could put a unique number on each token, and check it is not spent twice, but that would allow the gate attendant to tell the bartender which numbers were linked to which person. So, we need cryptography.

When another website presents a challenge to you, you provide your Privacy Pass token and are then allowed to view a gallery of beautiful cat pictures. The difference with the festival is this challenge might be interactive, which would be similar to the bartender giving you a numbered ticket which would have to be signed by the agent before getting a drink. The website owner can verify that the token is valid but has no way of tracing or connecting the user back to the action that provided them with the Privacy Pass tokens. With Privacy Pass terminology, you are a Client, the website is an Origin, the agent is an Attester, and the bar an Issuer. The next section goes through these in more detail.

Privacy Pass protocol

Privacy Pass specifies an extensible protocol for creating and redeeming anonymous and transferable tokens. In fact, Apple has their own implementation with Private Access Tokens (PAT), and later we will describe another implementation with the Silk browser extension. Given PAT was the first to implement the IETF defined protocol, Privacy Pass is sometimes referred to as PAT in the literature.

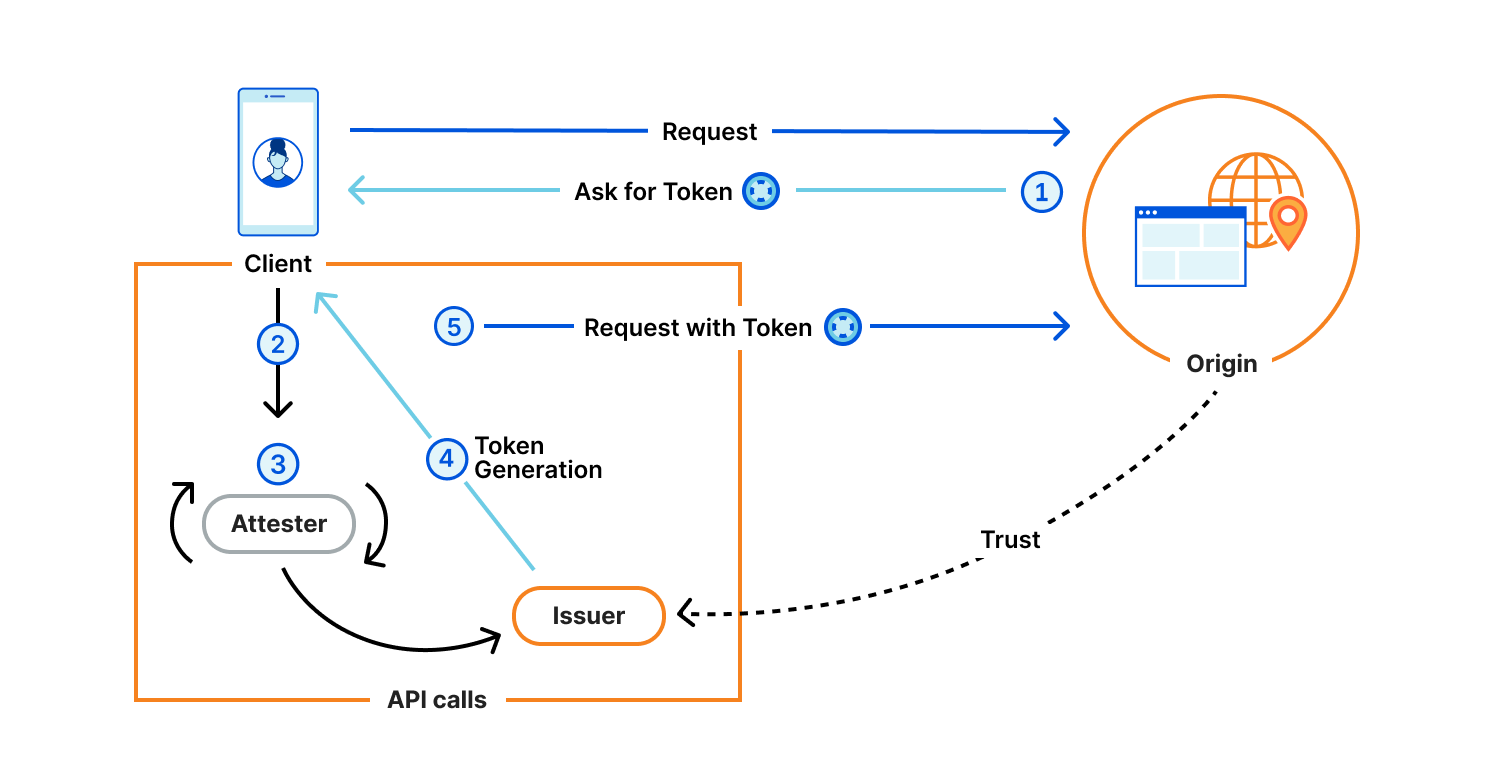

The protocol is generic, and defines four components:

- Client: Web user agent with a Privacy Pass enabled browser. This could be your Apple device with PAT, or your web browser with the Silk extension installed. Typically, this is the actor who is requesting content and is asked to share some attribute of themselves.

- Origin: Serves content requested by the Client. The Origin trusts one or more Issuers, and presents Privacy Pass challenges to the Client. For instance, Cloudflare Managed Challenge is a Privacy Pass origin serving two Privacy Pass challenges: one for Apple PAT Issuer, one for Cloudflare Research Issuer.

- Issuer: Signs Privacy Pass tokens upon request from a trusted party, either an Attester or a Client depending on the deployment model. Different Issuers have their own set of trusted parties, depending on the security level they are looking for, as well as their privacy considerations. An Issuer validating device integrity should use different methods that vouch for this attribute to acknowledge the diversity of Client configurations.

- Attester: Verifies an attribute of the Client and when satisfied requests a signed Privacy Pass token from the Issuer to pass back to the Client. Before vouching for the Client, an Attester may ask the Client to complete a specific task. This task could be a CAPTCHA, a location check, or age verification or some other check that will result in a single binary result. The Privacy Pass token will then share this one-bit of information in an unlinkable manner.

They interact as illustrated below.

Let’s dive into what’s really happening with an example. The User wants to access an Origin, say store.example.com. This website has suffered attacks or abuse in the past, and the site is using Privacy Pass to help avoid these going forward. To that end, the Origin returns an authentication request to the Client: WWW-Authenticate: PrivateToken challenge="A==",token-key="B==". In this way, the Origin signals that it accepts tokens from the Issuer with public key “B==” to satisfy the challenge. That Issuer in turn trusts reputable Attesters to vouch for the Client not being an attacker by means of the presence of a cookie, CAPTCHA, Turnstile, or CAP challenge for example. For accessibility reasons for our example, let us say that the Client likely prefers the Turnstile method. The User’s browser prompts them to solve a Turnstile challenge. On success, it contacts the Issuer “B==” with that solution, and then replays the initial requests to store.example.com, this time sending along the token header Authorization: PrivateToken token="C==", which the Origin accepts and returns your desired content to the Client. And that’s it.

We’ve described the Privacy Pass authentication protocol. While Basic authentication (RFC 7671) asks you for a username and a password, the PrivateToken authentication scheme allows the browser to be more flexible on the type of check, while retaining privacy. The Origin store.example.com does not know your attestation method, they just know you are reputable according to the token issuer. In the same spirit, the Issuer “B==” does not see your IP, nor the website you are visiting. This separation between issuance and redemption, also referred to as unlinkability, is what makes Privacy Pass private.

Demo time

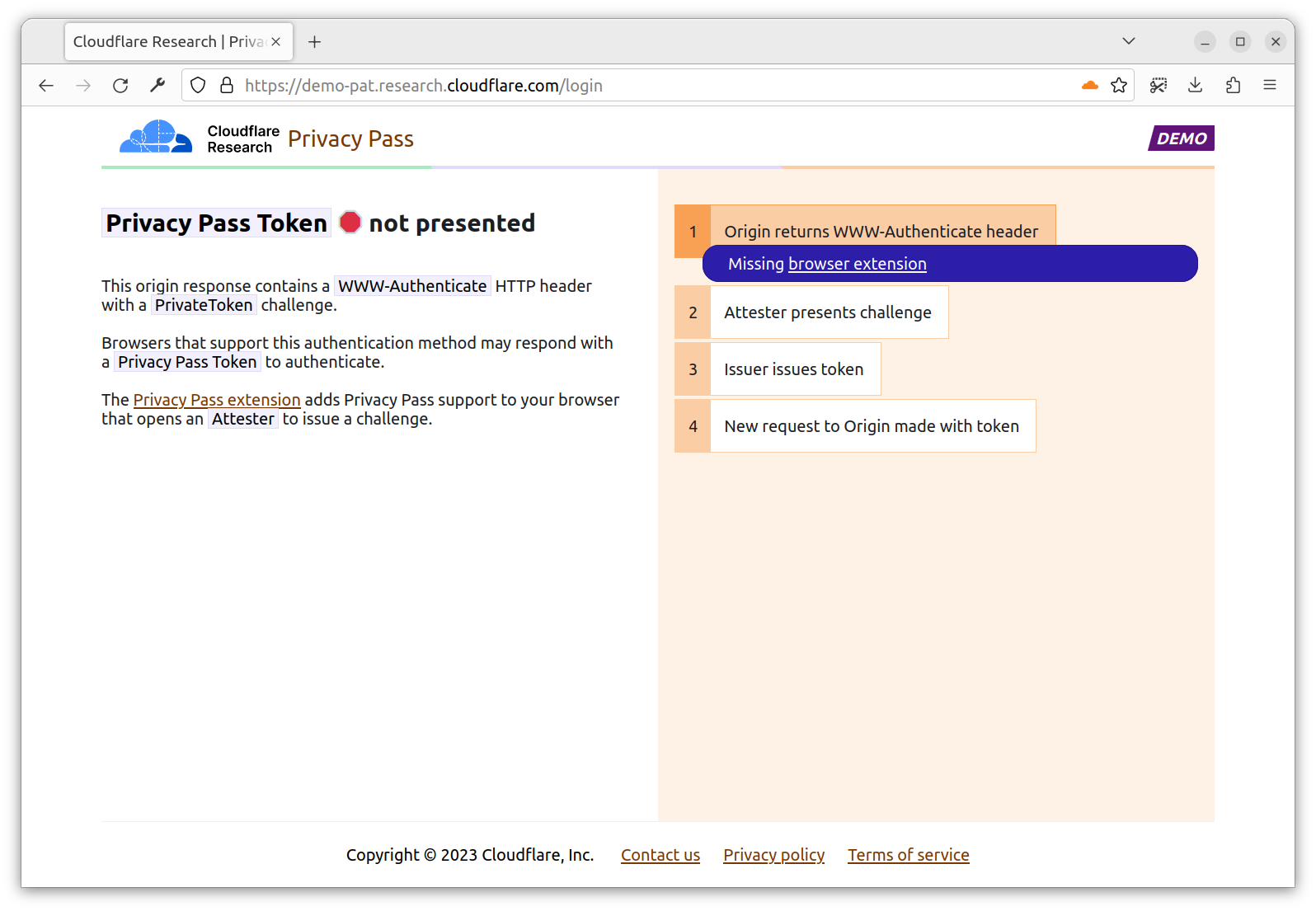

To put the above in practice, let’s see how the protocol works with Silk, a browser extension providing Privacy Pass support. First, download the relevant Chrome or Firefox extension.

Then, head to https://demo-pat.research.cloudflare.com/login. The page returns a 401 Privacy Pass Token not presented. In fact, the origin expects you to perform a PrivateToken authentication. If you don’t have the extension installed, the flow stops here. If you have the extension installed, the extension is going to orchestrate the flow required to get you a token requested by the Origin.

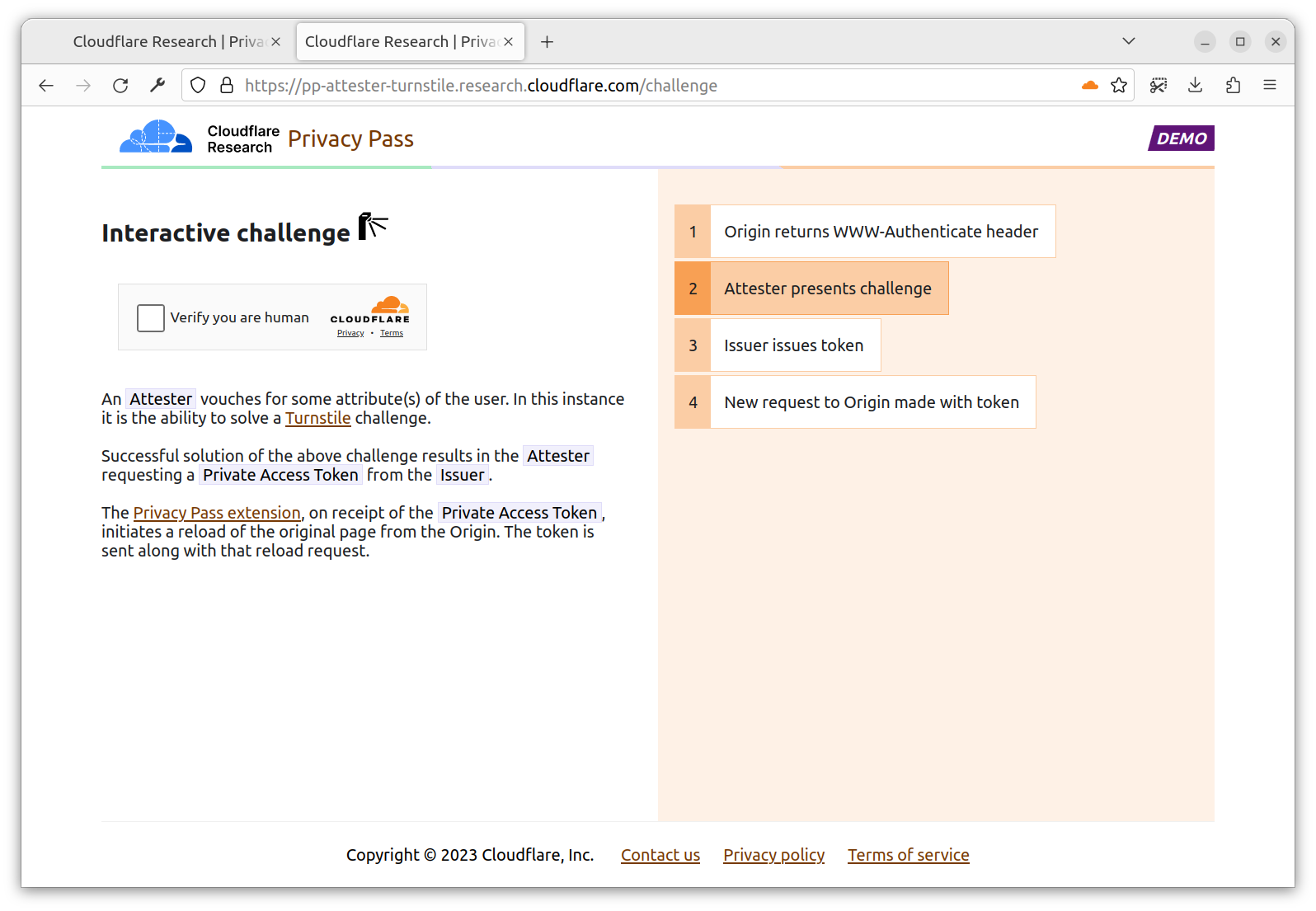

With the extension installed, you are directed to a new tab https://pp-attester-turnstile.research.cloudflare.com/challenge. This is a page provided by an Attester able to deliver you a token signed by the Issuer request by the Origin. In this case, the Attester checks you’re able to solve a Turnstile challenge.

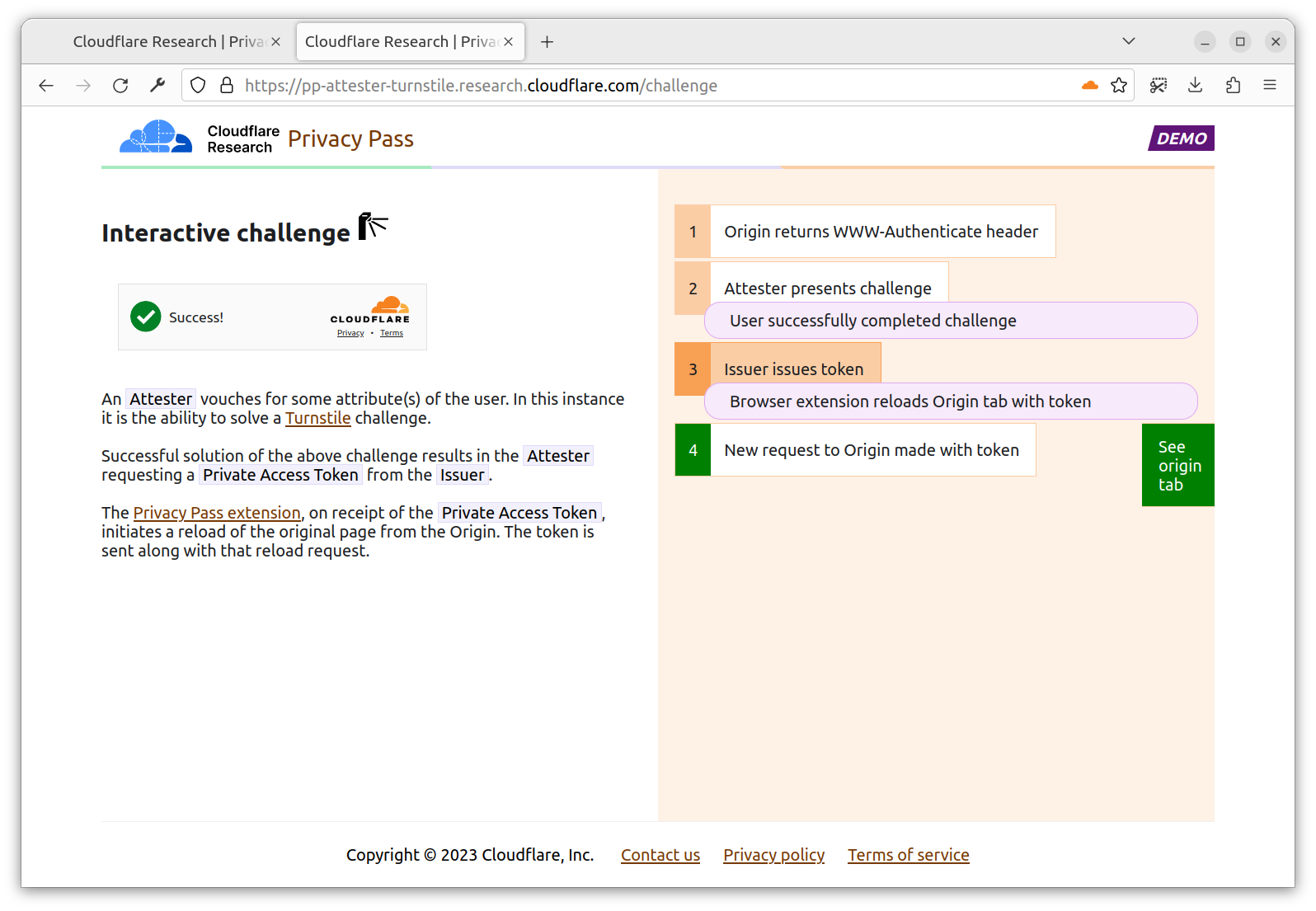

You click, and that’s it. The Turnstile challenge solution is sent to the Attester, which upon validation, sends back a token from the requested Issuer. This page appears for a very short time, as once the extension has the token, the challenge page is no longer needed.

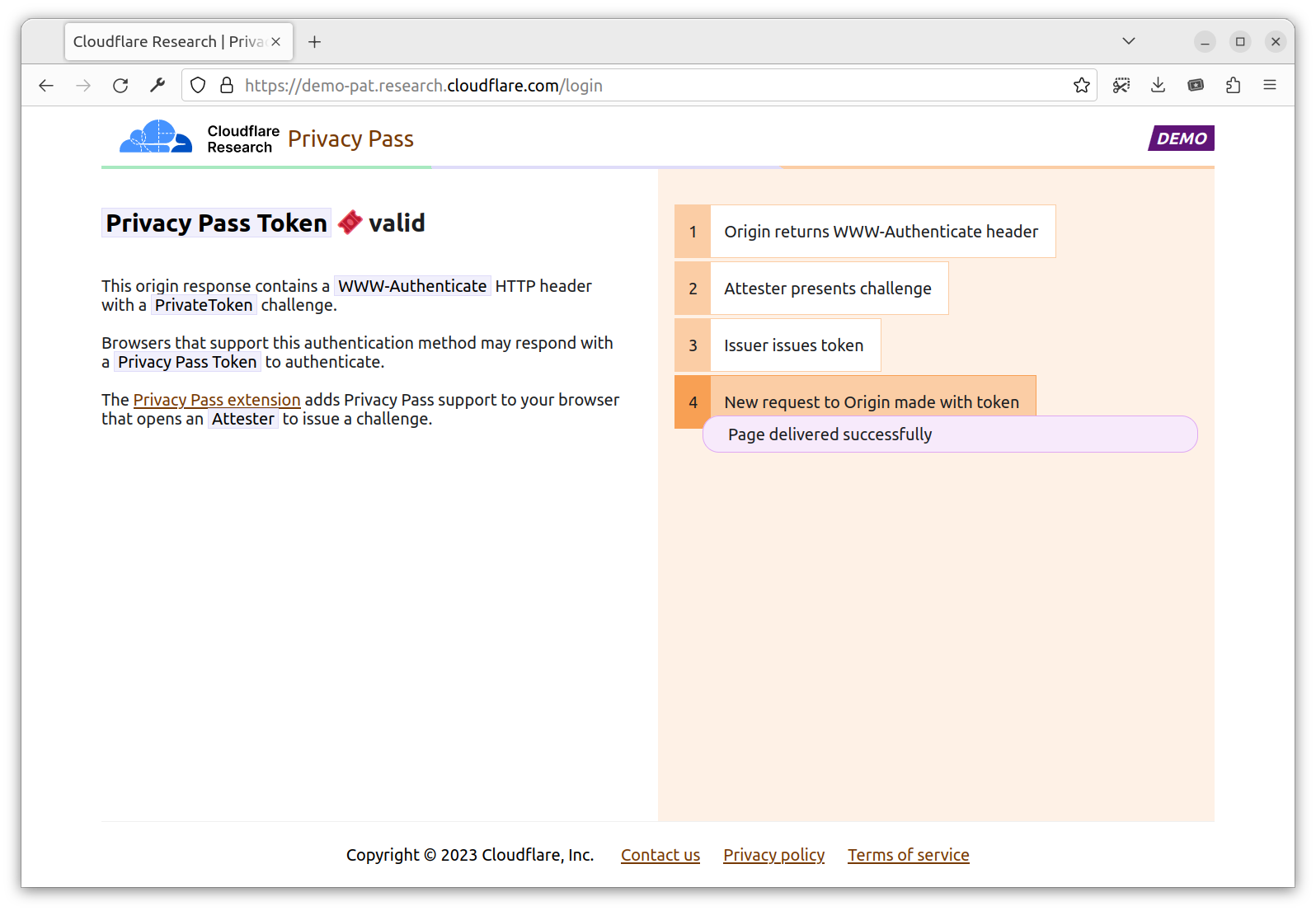

The extension, now having a token requested by the Origin, sends your initial request for a second time, with an Authorization header containing a valid Issuer PrivateToken. Upon validation, the Origin allows you in with a 200 Privacy Pass Token valid!

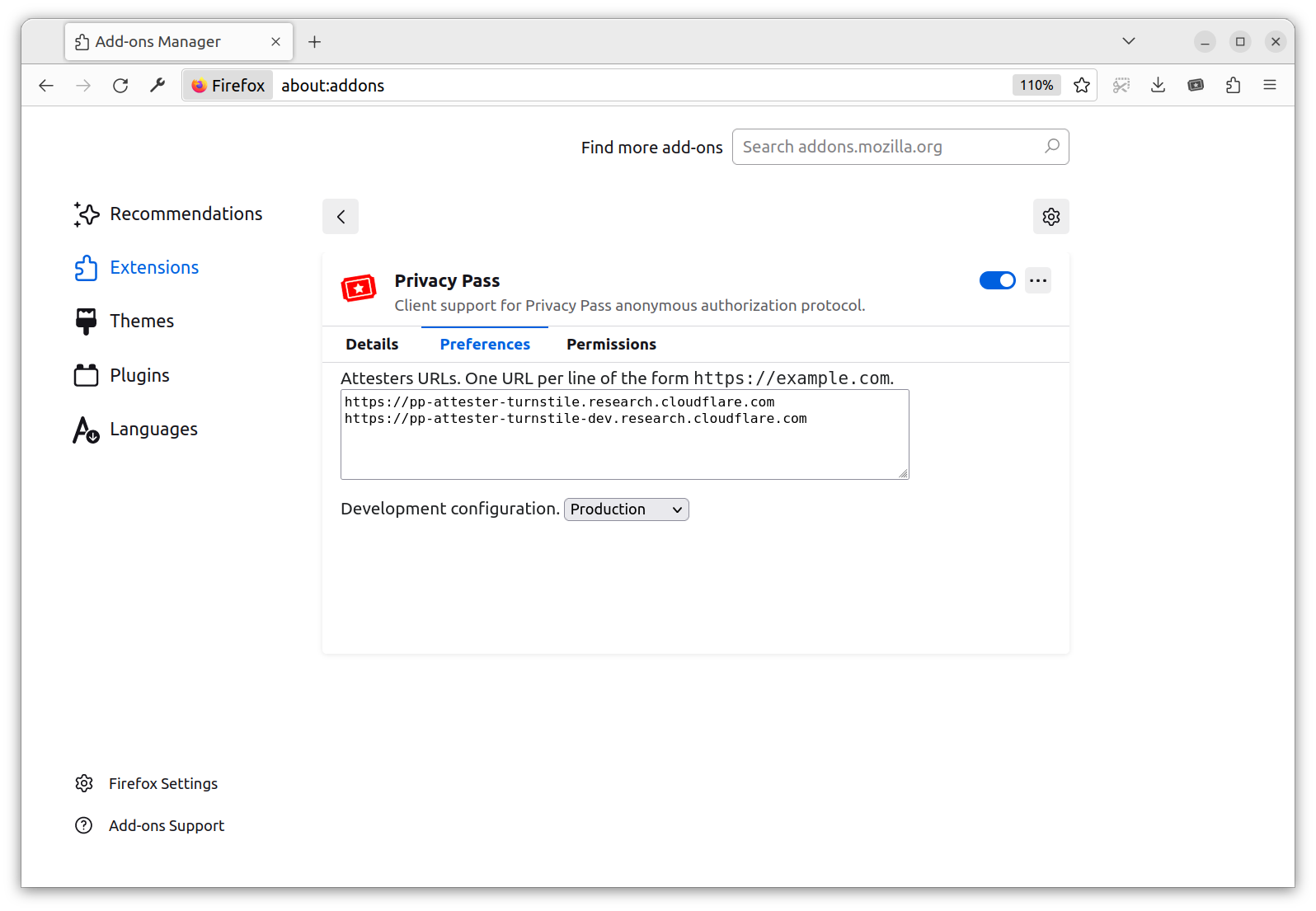

If you want to check behind the scenes, you can right-click on the extension logo and go to the preference/options page. It contains a list of attesters trusted by the extension, one per line. You can add your own attestation method (API described below). This allows the Client to decide on their preferred attestation methods.

Privacy Pass protocol — extended

The Privacy Pass protocol is new and not a standard yet, which implies that it’s not uniformly supported on all platforms. To improve flexibility beyond the existing standard proposal, we are introducing two mechanisms: an API for Attesters, and a replay API for web clients. The API for attesters allows developers to build new attestation methods, which only need to provide their URL to interface with the Silk browser extension. The replay API for web clients is a mechanism to enable websites to cooperate with the extension to make PrivateToken authentication work on browsers with Chrome user agents.

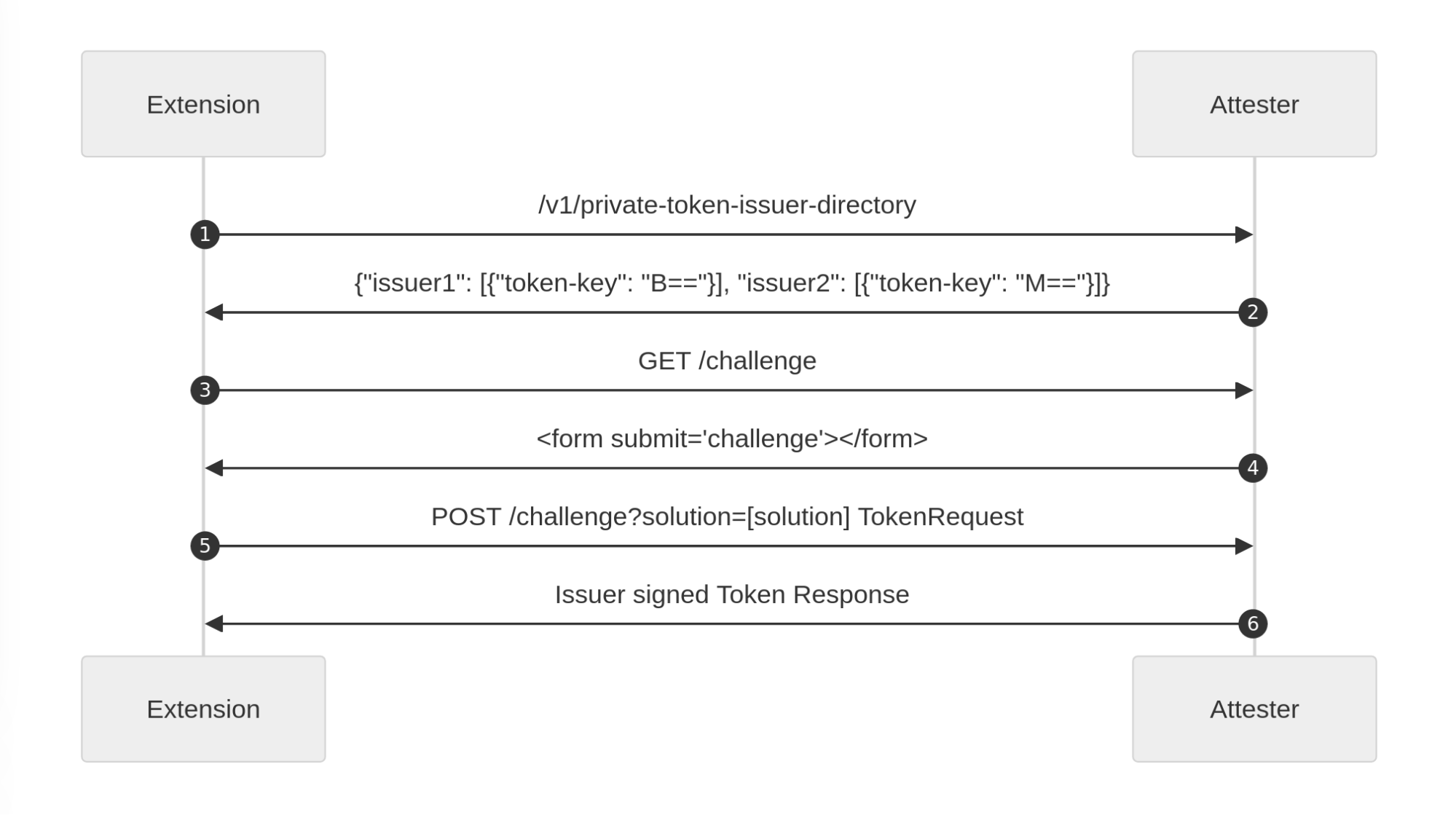

Because more than one Attester may be supported on your machine, your Client needs to understand which Attester to use depending on the requested Issuer. As mentioned before, you as the Client do not communicate directly with the Issuer because you don’t necessarily know their relation with the attester, so you cannot retrieve its public key. To this end, the Attester API exposes all Issuers reachable by the said Attester via an endpoint: /v1/private-token-issuer-directory. This way, your client selects an appropriate Attester – one in relation with an Issuer that the Origin trusts, before triggering a validation.

In addition, we propose a replay API. Its goal is to allow clients to fetch a resource a second time if the first response presented a Privacy pass challenge. Some platforms do this automatically, like Silk on Firefox, but some don’t. That’s the case with the Silk Chrome extension for instance, which in its support of manifest v3 cannot block requests and only supports Basic authentication in the onAuthRequired extension event. The Privacy Pass Authentication scheme proposes the request to be sent once to get a challenge, and then a second time to get the actual resource. Between these requests to the Origin, the platform orchestrates the issuance of a token. To keep clients informed about the state of this process, we introduce a private-token-client-replay: UUID header alongside WWW-Authenticate. Using a platform defined endpoint, this UUID informs web clients of the current state of authentication: pending, fulfilled, not-found.

To learn more about how you can use these today, and to deploy your own attestation method, read on.

How to use Privacy Pass today?

As seen in the section above, Privacy Pass is structured around four components: Origin, Client, Attester, Issuer. That’s why we created four repositories: cloudflare/pp-origin, cloudflare/pp-browser-extension, cloudflare/pp-attester, cloudflare/pp-issuer. In addition, the underlying cryptographic libraries are available cloudflare/privacypass-ts, cloudflare/blindrsa-ts, and cloudflare/voprf-ts. In this section, we dive into how to use each one of these depending on your use case.

Note: All examples below are designed in JavaScript and targeted at Cloudflare Workers. Privacy Pass is also implemented in other languages and can be deployed with a configuration that suits your needs.

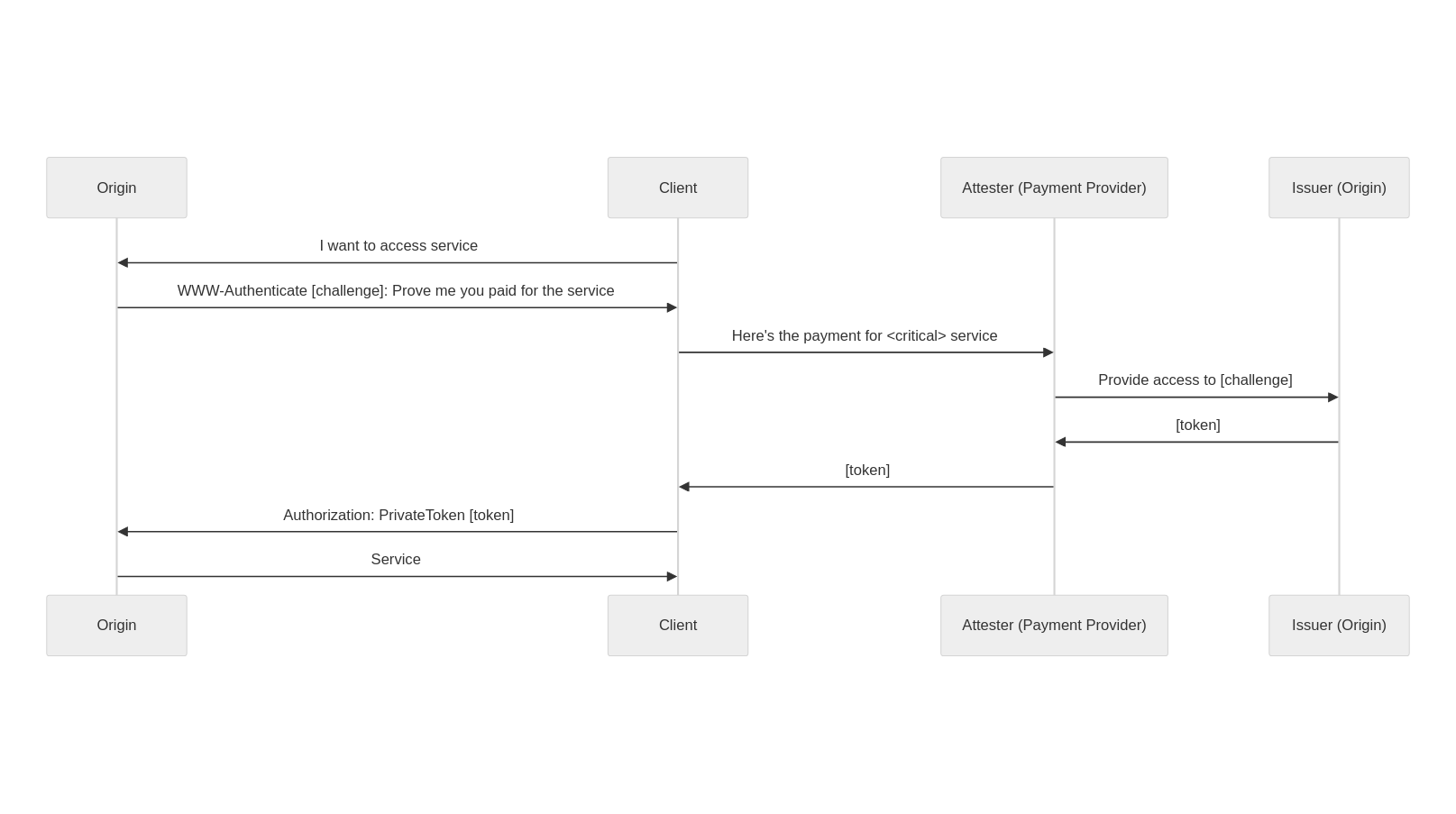

As an Origin – website owners, service providers

You are an online service that people critically rely upon (health or messaging for instance). You want to provide private payment options to users to maintain your users’ privacy. You only have one subscription tier at $10 per month. You have heard people are making privacy preserving apps, and want to use the latest version of Privacy Pass.

To access your service, users are required to prove they’ve paid for the service through a payment provider of their choosing (that you deem acceptable). This payment provider acknowledges the payment and requests a token for the user to access the service. As a sequence diagram, it looks as follows:

To implement it in Workers, we rely on the @cloudflare/privacypass-ts library, which can be installed by running:

npm i @cloudflare/privacypass-ts

This section is going to focus on the Origin work. We assume you have an Issuer up and running, which is described in a later section.

The Origin defines two flows:

- User redeeming token

- User requesting a token issuance

import { Client } from '@cloudflare/privacypass-ts'

const issuer = 'static issuer key'

const handleRedemption => (req) => {

const token = TokenResponse.parse(req.headers.get('authorization'))

const isValid = token.verify(issuer.publicKey)

}

const handleIssuance = () => {

return new Response('Please pay to access the service', {

status: 401,

headers: { 'www-authenticate': 'PrivateToken challenge=, token-key=, max-age=300' }

})

}

const handleAuth = (req) => {

const authorization = req.headers.get('authorization')

if (authorization.startsWith(`PrivateToken token=`)) {

return handleRedemption(req)

}

return handleIssuance(req)

}

export default {

fetch(req: Request) {

return handleAuth(req)

}

}

From the user’s perspective, the overhead is minimal. Their client (possibly the Silk browser extension) receives a WWW-Authenticate header with the information required for a token issuance. Then, depending on their client configuration, they are taken to the payment provider of their choice to validate their access to the service.

With a successful response to the PrivateToken challenge a session is established, and the traditional web service flow continues.

As an Attester – CAPTCHA providers, authentication provider

You are the author of a new attestation method, such as CAP, a new CAPTCHA mechanism, or a new way to validate cookie consent. You know that website owners already use Privacy Pass to trigger such challenges on the user side, and an Issuer is willing to trust your method because it guarantees a high security level. In addition, because of the Privacy Pass protocol you never see which website your attestation is being used for.

So you decide to expose your attestation method as a Privacy Pass Attester. An Issuer with public key B== trusts you, and that’s the Issuer you are going to request a token from. You can check that with the Yes/No Attester below, whose code is on Cloudflare Workers playground

const ISSUER_URL = 'https://pp-issuer-public.research.cloudflare.com/token-request'

const b64ToU8 = (b) => Uint8Array.from(atob(b), c => c.charCodeAt(0))

const handleGetChallenge = (req) => {

return new Response(`

<html>

<head>

<title>Challenge Response</title>

</head>

<body>

<button onclick="sendResponse('Yes')">Yes</button>

<button onclick="sendResponse('No')">No</button>

</body>

<script>

function sendResponse(choice) {

fetch(location.href, { method: 'POST', headers: { 'private-token-attester-data': choice } })

}

</script>

</html>

`, { status: 401, headers: { 'content-type': 'text/html' } })

}

const handlePostChallenge = (req) => {

const choice = req.headers.get('private-token-attester-data')

if (choice !== 'Yes') {

return new Response('Unauthorised', { status: 401 })

}

// hardcoded token request

// debug here https://pepe-debug.research.cloudflare.com/?challenge=PrivateToken%20challenge=%22AAIAHnR1dG9yaWFsLmNsb3VkZmxhcmV3b3JrZXJzLmNvbSBE-oWKIYqMcyfiMXOZpcopzGBiYRvnFRP3uKknYPv1RQAicGVwZS1kZWJ1Zy5yZXNlYXJjaC5jbG91ZGZsYXJlLmNvbQ==%22,token-key=%22MIIBUjA9BgkqhkiG9w0BAQowMKANMAsGCWCGSAFlAwQCAqEaMBgGCSqGSIb3DQEBCDALBglghkgBZQMEAgKiAwIBMAOCAQ8AMIIBCgKCAQEApqzusqnywE_3PZieStkf6_jwWF-nG6Es1nn5MRGoFSb3aXJFDTTIX8ljBSBZ0qujbhRDPx3ikWwziYiWtvEHSLqjeSWq-M892f9Dfkgpb3kpIfP8eBHPnhRKWo4BX_zk9IGT4H2Kd1vucIW1OmVY0Z_1tybKqYzHS299mvaQspkEcCo1UpFlMlT20JcxB2g2MRI9IZ87sgfdSu632J2OEr8XSfsppNcClU1D32iL_ETMJ8p9KlMoXI1MwTsI-8Kyblft66c7cnBKz3_z8ACdGtZ-HI4AghgW-m-yLpAiCrkCMnmIrVpldJ341yR6lq5uyPej7S8cvpvkScpXBSuyKwIDAQAB%22

const body = b64ToU8('AALoAYM+fDO53GVxBRuLbJhjFbwr0uZkl/m3NCNbiT6wal87GEuXuRw3iZUSZ3rSEqyHDhMlIqfyhAXHH8t8RP14ws3nQt1IBGE43Q9UinwglzrMY8e+k3Z9hQCEw7pBm/hVT/JNEPUKigBYSTN2IS59AUGHEB49fgZ0kA6ccu9BCdJBvIQcDyCcW5LCWCsNo57vYppIVzbV2r1R4v+zTk7IUDURTa4Mo7VYtg1krAWiFCoDxUOr+eTsc51bWqMtw2vKOyoM/20Wx2WJ0ox6JWdPvoBEsUVbENgBj11kB6/L9u2OW2APYyUR7dU9tGvExYkydXOfhRFJdKUypwKN70CiGw==')

// You can perform some check here to confirm the body is a valid token request

console.log('requesting token for tutorial.cloudflareworkers.com')

return fetch(ISSUER_URL, {

method: 'POST',

headers: { 'content-type': 'application/private-token-request' },

body: body,

})

}

const handleIssuerDirectory = async () => {

// These are fake issuers

// Issuer data can be fetch at https://pp-issuer-public.research.cloudflare.com/.well-known/private-token-issuer-directory

const TRUSTED_ISSUERS = {

"issuer1": { "token-keys": [{ "token-type": 2, "token-key": "A==" }] },

"issuer2": { "token-keys": [{ "token-type": 2, "token-key": "B==" }] },

}

return new Response(JSON.stringify(TRUSTED_ISSUERS), { headers: { "content-type": "application/json" } })

}

const handleRequest = (req) => {

const pathname = new URL(req.url).pathname

console.log(pathname, req.url)

if (pathname === '/v1/challenge') {

if (req.method === 'POST') {

return handlePostChallenge(req)

}

return handleGetChallenge(req)

}

if (pathname === '/v1/private-token-issuer-directory') {

return handleIssuerDirectory()

}

return new Response('Not found', { status: 404 })

}

addEventListener('fetch', event => {

event.respondWith(handleRequest(event.request))

})

The validation method above is simply checking if the user selected yes. Your method might be more complex, the wrapping stays the same.

Because users might have multiple Attesters configured for a given Issuer, we recommend your Attester implements one additional endpoint exposing the keys of the issuers you are in contact with. You can try this code on Cloudflare Workers playground.

const handleIssuerDirectory = () => {

const TRUSTED_ISSUERS = {

"issuer1": { "token-keys": [{ "token-type": 2, "token-key": "A==" }] },

"issuer2": { "token-keys": [{ "token-type": 2, "token-key": "B==" }] },

}

return new Response(JSON.stringify(TRUSTED_ISSUERS), { headers: { "content-type": "application/json" } })

}

export default {

fetch(req: Request) {

const pathname = new URL(req.url).pathname

if (pathname === '/v1/private-token-issuer-directory') {

return handleIssuerDirectory()

}

}

}

Et voilà. You have an Attester that can be used directly with the Silk browser extension (Firefox, Chrome). As you progress through your deployment, it can also be directly integrated into your applications.

If you would like to have a more advanced Attester and deployment pipeline, look at cloudflare/pp-attester template.

As an Issuer – foundation, consortium

We’ve mentioned the Issuer multiple times already. The role of an Issuer is to select a set of Attesters it wants to operate with, and communicate its public key to Origins. The whole cryptographic behavior of an Issuer is specified by the IETF draft. In contrast to the Client and Attesters which have discretionary behavior, the Issuer is fully standardized. Their opportunity is to choose a signal that is strong enough for the Origin, while preserving privacy of Clients.

Cloudflare Research is operating a public Issuer for experimental purposes to use on https://pp-issuer-public.research.cloudflare.com. It is the simplest solution to start experimenting with Privacy Pass today. Once it matures, you can consider joining a production Issuer, or deploying your own.

To deploy your own, you should:

git clone github.com/cloudflare/pp-issuer

Update wrangler.toml with your Cloudflare Workers account id and zone id. The open source Issuer API works as follows:

- /.well-known/private-token-issuer-directory returns the issuer configuration. Note it does not expose non-standard token-key-legacy

- /token-request returns a token. This endpoint should be gated (by Cloudflare Access for instance) to only allow trusted attesters to call it

- /admin/rotate to generate a new public key. This should only be accessible by your team, and be called prior to the issuer being available.

Then, wrangler publish, and you’re good to onboard Attesters.

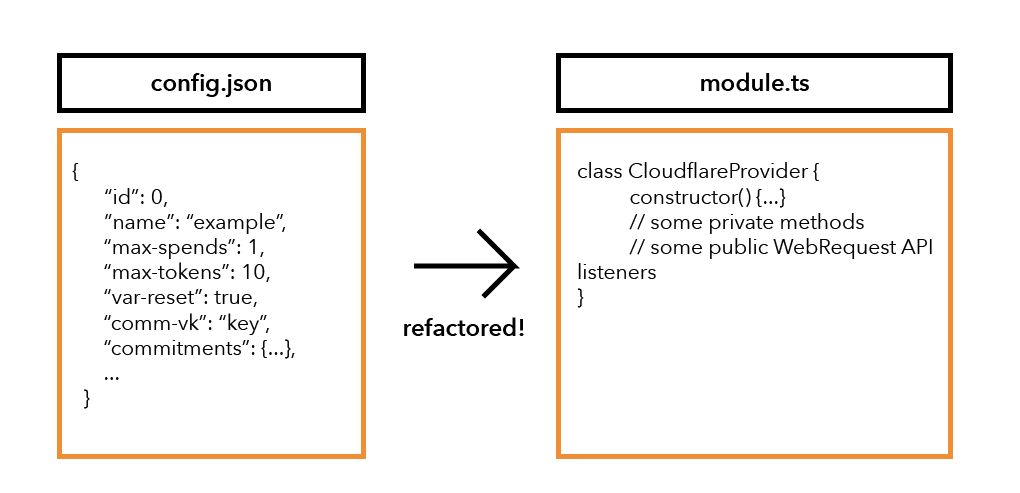

Development of Silk extension

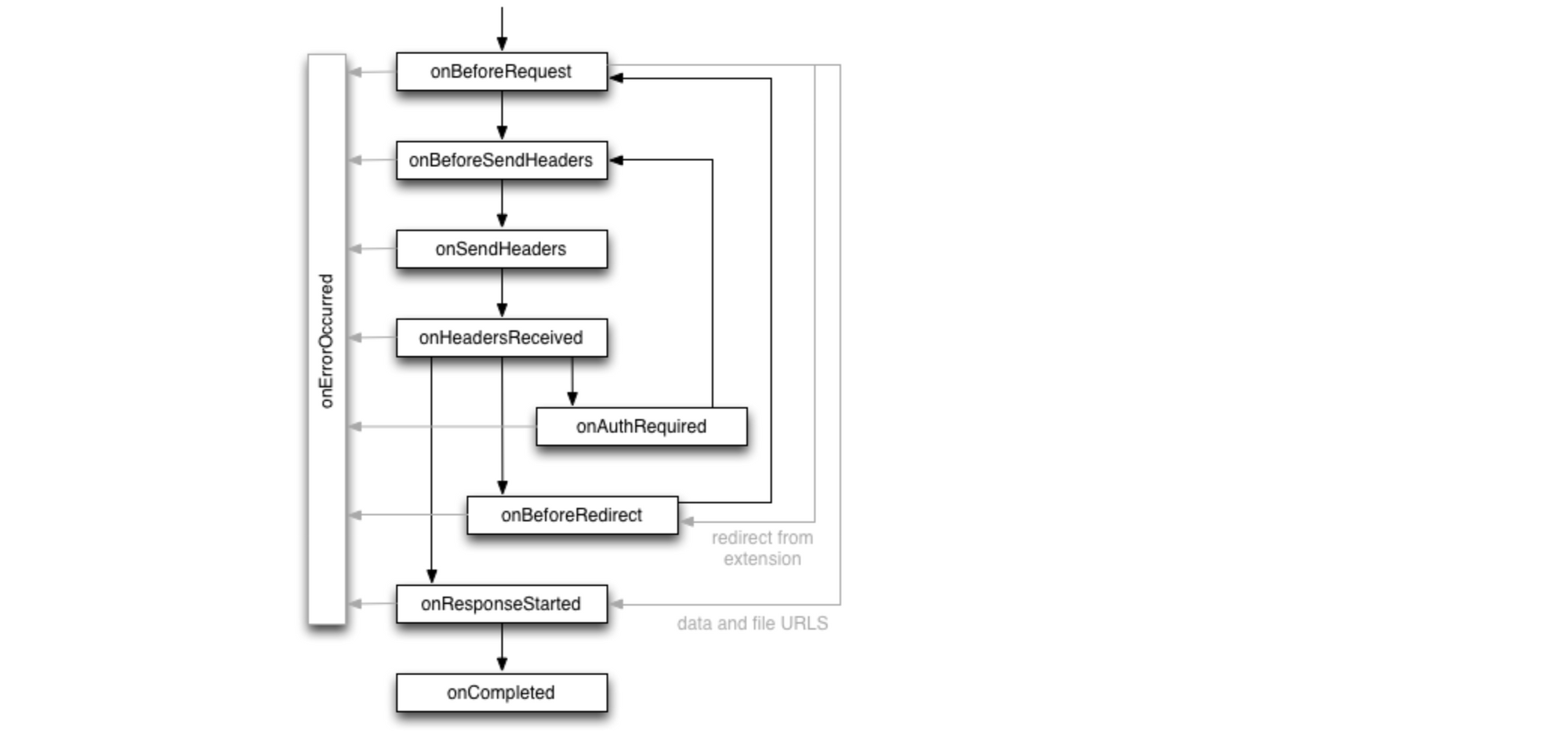

Just like the protocol, the browser technology on which Privacy Pass was proven viable has changed as well. For 5 years, the protocol got deployed along with a browser extension for Chrome and Firefox. In 2021, Chrome released a new version of extension configurations, usually referred to as Manifest version 3 (MV3). Chrome also started enforcing this new configuration for all newly released extensions.

Privacy Pass the extension is based on an agreed upon Privacy Pass authentication protocol. Briefly looking at Chrome’s API documentation, we should be able to use the onAuthRequired event. However, with PrivateToken authentication not yet being standard, there are no hooks provided by browsers for extensions to add logic to this event.

The approach we decided to use is to define a client side replay API. When a response comes with 401 WWW-Authenticate PrivateToken, the browser lets it through, but triggers the private token redemption flow. The original page is notified when a token has been retrieved, and replays the request. For this second request, the browser is able to attach an authorization token, and the request succeeds. This is an active replay performed by the client, rather than a transparent replay done by the platform. A specification is available on GitHub.

We are looking forward to the standard progressing, and simplifying this part of the project. This should improve diversity in attestation methods. As we see in the next section, this is key to identifying new signals that can be leveraged by origins.

A standard for anonymous credentials

IP remains as a key identifier in the anti abuse system. At the same time, IP fingerprinting techniques have become a bigger concern and platforms have started to remove some of these ways of tracking users. To enable anti abuse systems to not rely on IP, while ensuring user privacy, Privacy Pass offers a reasonable alternative to deal with potentially abusive or suspicious traffic. The attestation methods vary and can be chosen as needed for a particular deployment. For example, Apple decided to back their attestation with hardware when using Privacy Pass as the authorization technology for iCloud Private Relay. Another example is Cloudflare Research which decided to deploy a Turnstile attester to signal a successful solve for Cloudflare’s challenge platform.

In all these deployments, Privacy Pass-like technology has allowed for specific bits of information to be shared. Instead of sharing your location, past traffic, and possibly your name and phone number simply by connecting to a website, your device is able to prove specific information to a third party in a privacy preserving manner. Which user information and attestation methods are sufficient to prevent abuse is an open question. We are looking to empower researchers with the release of this software to help in the quest for finding these answers. This could be via new experiments such as testing out new attestation methods, or fostering other privacy protocols by providing a framework for specific information sharing.

Future recommendations

Just as we expect this latest version of Privacy Pass to lead to new applications and ideas we also expect further evolution of the standard and the clients that use it. Future development of Privacy Pass promises to cover topics like batch token issuance and rate limiting. From our work building and deploying this version of Privacy Pass we have encountered limitations that we expect to be resolved in the future as well.

The division of labor between Attesters and Issuers and the clear directions of trust relationships between the Origin and Issuer, and the Issuer and Attester make reasoning about the implications of a breach of trust clear. Issuers can trust more than one Attester, but since many current deployments of Privacy Pass do not identify the Attester that lead to issuance, a breach of trust in one Attester would render all tokens issued by any Issuer that trusts the Attester untrusted. This is because it would not be possible to tell which Attester was involved in the issuance process. Time will tell if this promotes a 1:1 correspondence between Attesters and Issuers.

The process of developing a browser extension supported by both Firefox and Chrome-based browsers can at times require quite baroque (and brittle) code paths. Privacy Pass the protocol seems a good fit for an extension of the webRequest.onAuthRequired browser event. Just as Privacy Pass appears as an alternate authentication message in the WWW-Authenticate HTTP header, browsers could fire the onAuthRequired event for Private Token authentication too and include and allow request blocking support within the onAuthRequired event. This seems a natural evolution of the use of this event which currently is limited to the now rather long-in-the-tooth Basic authentication.

Conclusion

Privacy Pass provides a solution to one of the longstanding challenges of the web: anonymous authentication. By leveraging cryptography, the protocol allows websites to get the information they need from users, and solely this information. It’s already used by millions to help distinguish human requests from automated bots in a manner that is privacy protective and often seamless. We are excited by the protocol’s broad and growing adoption, and by the novel use cases that are unlocked by this latest version.

Cloudflare’s Privacy Pass implementations are available on GitHub, and are compliant with the standard. We have open-sourced a set of templates that can be used to implement Privacy Pass Origins, Issuers, and Attesters, which leverage Cloudflare Workers to get up and running quickly.

For those looking to try Privacy Pass out for themselves right away, download the Silk – Privacy Pass Client browser extensions (Firefox, Chrome, GitHub) and start browsing a web with fewer bot checks today.