Post Syndicated from Tom Lianza original https://blog.cloudflare.com/a-byzantine-failure-in-the-real-world/

An analysis of the Cloudflare API availability incident on 2020-11-02

When we review design documents at Cloudflare, we are always on the lookout for Single Points of Failure (SPOFs). Eliminating these is a necessary step in architecting a system you can be confident in. Ironically, when you’re designing a system with built-in redundancy, you spend most of your time thinking about how well it functions when that redundancy is lost.

On November 2, 2020, Cloudflare had an incident that impacted the availability of the API and dashboard for six hours and 33 minutes. During this incident, the success rate for queries to our API periodically dipped as low as 75%, and the dashboard experience was as much as 80 times slower than normal. While Cloudflare’s edge is massively distributed across the world (and kept working without a hitch), Cloudflare’s control plane (API & dashboard) is made up of a large number of microservices that are redundant across two regions. For most services, the databases backing those microservices are only writable in one region at a time.

Each of Cloudflare’s control plane data centers has multiple racks of servers. Each of those racks has two switches that operate as a pair—both are normally active, but either can handle the load if the other fails. Cloudflare survives rack-level failures by spreading the most critical services across racks. Every piece of hardware has two or more power supplies with different power feeds. Every server that stores critical data uses RAID 10 redundant disks or storage systems that replicate data across at least three machines in different racks, or both. Redundancy at each layer is something we review and require. So—how could things go wrong?

In this post we present a timeline of what happened, and how a difficult failure mode known as a Byzantine fault played a role in a cascading series of events.

2020-11-02 14:43 UTC: Partial Switch Failure

At 14:43, a network switch started misbehaving. Alerts began firing about the switch being unreachable to pings. The device was in a partially operating state: network control plane protocols such as LACP and BGP remained operational, while others, such as vPC, were not. The vPC link is used to synchronize ports across multiple switches, so that they appear as one large, aggregated switch to servers connected to them. At the same time, the data plane (or forwarding plane) was not processing and forwarding all the packets received from connected devices.

This failure scenario is completely invisible to the connected nodes, as each server only sees an issue for some of its traffic due to the load-balancing nature of LACP. Had the switch failed fully, all traffic would have failed over to the peer switch, as the connected links would’ve simply gone down, and the ports would’ve dropped out of the forwarding LACP bundles.

Six minutes later, the switch recovered without human intervention. But this odd failure mode led to further problems that lasted long after the switch had returned to normal operation.

2020-11-02 14:44 UTC: etcd Errors begin

The rack with the misbehaving switch included one server in our etcd cluster. We use etcd heavily in our core data centers whenever we need strongly consistent data storage that’s reliable across multiple nodes.

In the event that the cluster leader fails, etcd uses the RAFT protocol to maintain consistency and establish consensus to promote a new leader. In the RAFT protocol, cluster members are assumed to be either available or unavailable, and to provide accurate information or none at all. This works fine when a machine crashes, but is not always able to handle situations where different members of the cluster have conflicting information.

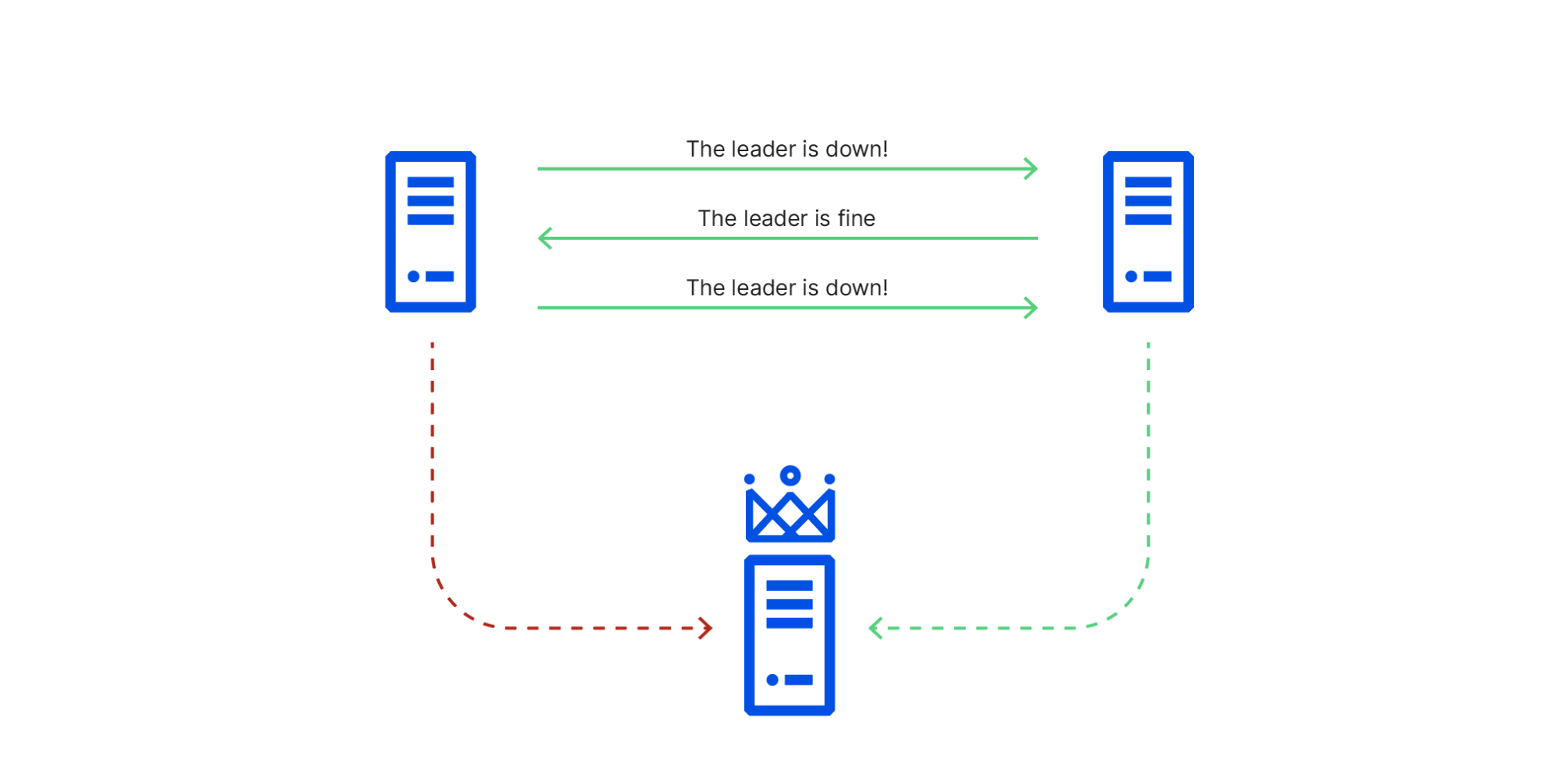

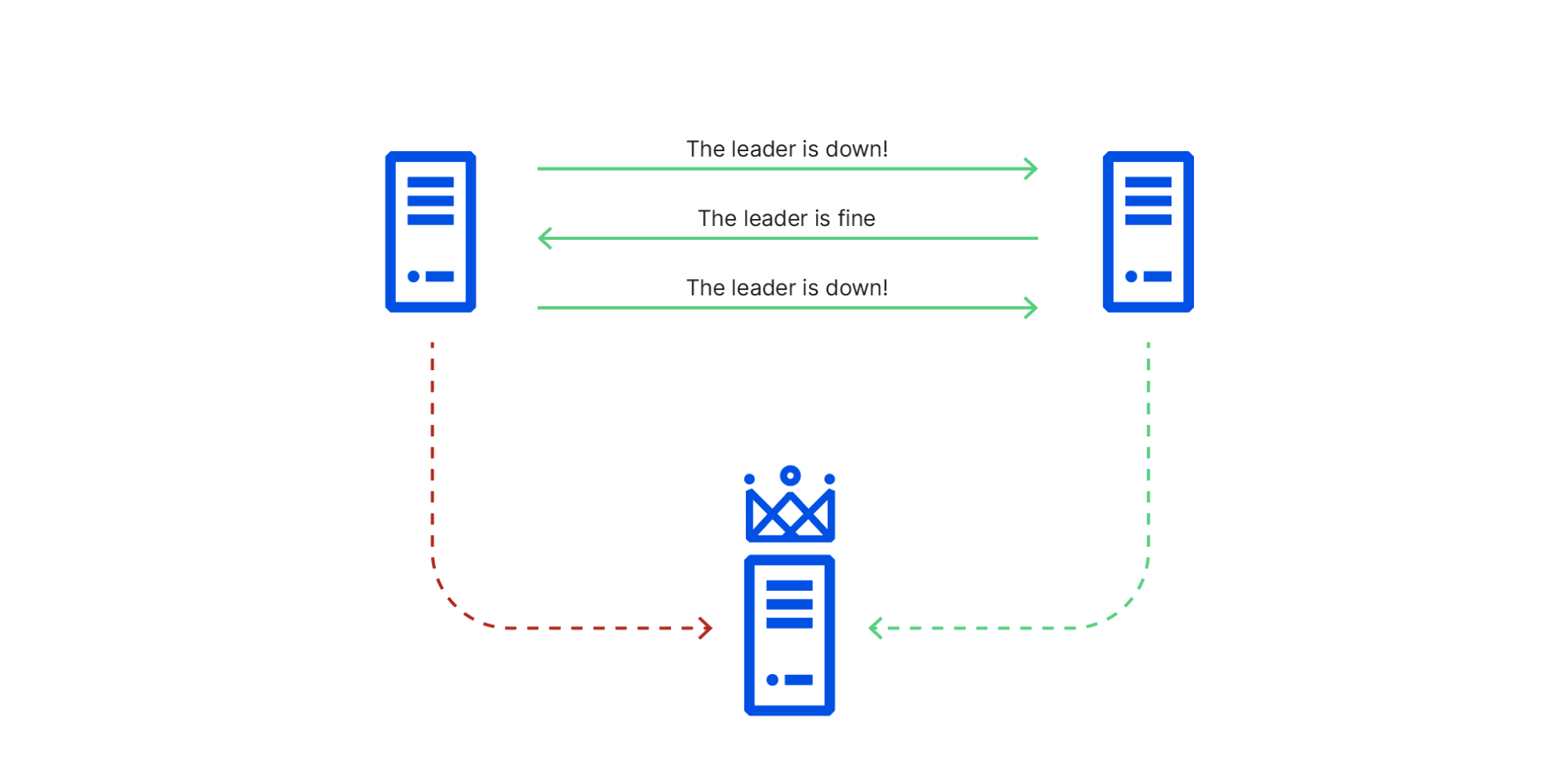

In this particular situation:

- Network traffic between node 1 (in the affected rack) and node 3 (the leader) was being sent through the switch in the degraded state,

- Network traffic between node 1 and node 2 were going through its working peer, and

- Network traffic between node 2 and node 3 was unaffected.

This caused cluster members to have conflicting views of reality, known in distributed systems theory as a Byzantine fault. As a consequence of this conflicting information, node 1 repeatedly initiated leader elections, voting for itself, while node 2 repeatedly voted for node 3, which it could still connect to. This resulted in ties that did not promote a leader node 1 could reach. RAFT leader elections are disruptive, blocking all writes until they’re resolved, so this made the cluster read-only until the faulty switch recovered and node 1 could once again reach node 3.

2020-11-02 14:45 UTC: Database system promotes a new primary database

Cloudflare’s control plane services use relational databases hosted across multiple clusters within a data center. Each cluster is configured for high availability. The cluster setup includes a primary database, a synchronous replica, and one or more asynchronous replicas. This setup allows redundancy within a data center. For cross-datacenter redundancy, a similar high availability secondary cluster is set up and replicated in a geographically dispersed data center for disaster recovery. The cluster management system leverages etcd for cluster member discovery and coordination.

When etcd became read-only, two clusters were unable to communicate that they had a healthy primary database. This triggered the automatic promotion of a synchronous database replica to become the new primary. This process happened automatically and without error or data loss.

There was a defect in our cluster management system that requires a rebuild of all database replicas when a new primary database is promoted. So, although the new primary database was available instantly, the replicas would take considerable time to become available, depending on the size of the database. For one of the clusters, service was restored quickly. Synchronous and asynchronous database replicas were rebuilt and started replicating successfully from primary, and the impact was minimal.

For the other cluster, however, performant operation of that database required a replica to be online. Because this database handles authentication for API calls and dashboard activities, it takes a lot of reads, and one replica was heavily utilized to spare the primary the load. When this failover happened and no replicas were available, the primary was overloaded, as it had to take all of the load. This is when the main impact started.

Reduce Load, Leverage Redundancy

At this point we saw that our primary authentication database was overwhelmed and began shedding load from it. We dialed back the rate at which we push SSL certificates to the edge, send emails, and other features, to give it space to handle the additional load. Unfortunately, because of its size, we knew it would take several hours for a replica to be fully rebuilt.

A silver lining here is that every database cluster in our primary data center also has online replicas in our secondary data center. Those replicas are not part of the local failover process, and were online and available throughout the incident. The process of steering read-queries to those replicas was not yet automated, so we manually diverted API traffic that could leverage those read replicas to the secondary data center. This substantially improved our API availability.

The Dashboard

The Cloudflare dashboard, like most web applications, has the notion of a user session. When user sessions are created (each time a user logs in) we perform some database operations and keep data in a Redis cluster for the duration of that user’s session. Unlike our API calls, our user sessions cannot currently be moved across the ocean without disruption. As we took actions to improve the availability of our API calls, we were unfortunately making the user experience on the dashboard worse.

This is an area of the system that is currently designed to be able to fail over across data centers in the event of a disaster, but has not yet been designed to work in both data centers at the same time. After a first period in which users on the dashboard became increasingly frustrated, we failed the authentication calls fully back to our primary data center, and kept working on our primary database to ensure we could provide the best service levels possible in that degraded state.

2020-11-02 21:20 UTC Database Replica Rebuilt

The instant the first database replica rebuilt, it put itself back into service, and performance resumed to normal levels. We re-ramped all of the services that had been turned down, so all asynchronous processing could catch up, and after a period of monitoring marked the end of the incident.

Redundant Points of Failure

The cascade of failures in this incident was interesting because each system, on its face, had redundancy. Moreover, no system fully failed—each entered a degraded state. That combination meant the chain of events that transpired was considerably harder to model and anticipate. It was frustrating yet reassuring that some of the possible failure modes were already being addressed.

A team was already working on fixing the limitation that requires a database replica rebuild upon promotion. Our user sessions system was inflexible in scenarios where we’d like to steer traffic around, and redesigning that was already in progress.

This incident also led us to revisit the configuration parameters we put in place for things that auto-remediate. In previous years, promoting a database replica to primary took far longer than we liked, so getting that process automated and able to trigger on a minute’s notice was a point of pride. At the same time, for at least one of our databases, the cure may be worse than the disease, and in fact we may not want to invoke the promotion process so quickly. Immediately after this incident we adjusted that configuration accordingly.

Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) is a hot research topic. Solutions have been known since 1982, but have had to choose between a variety of engineering tradeoffs, including security, performance, and algorithmic simplicity. Most general-purpose cluster management systems choose to forgo BFT entirely and use protocols based on PAXOS, or simplifications of PAXOS such as RAFT, that perform better and are easier to understand than BFT consensus protocols. In many cases, a simple protocol that is known to be vulnerable to a rare failure mode is safer than a complex protocol that is difficult to implement correctly or debug.

The first uses of BFT consensus were in safety-critical systems such as aircraft and spacecraft controls. These systems typically have hard real time latency constraints that require tightly coupling consensus with application logic in ways that make these implementations unsuitable for general-purpose services like etcd. Contemporary research on BFT consensus is mostly focused on applications that cross trust boundaries, which need to protect against malicious cluster members as well as malfunctioning cluster members. These designs are more suitable for implementing general-purpose services such as etcd, and we look forward to collaborating with researchers and the open source community to make them suitable for production cluster management.

We are very sorry for the difficulty the outage caused, and are continuing to improve as our systems grow. We’ve since fixed the bug in our cluster management system, and are continuing to tune each of the systems involved in this incident to be more resilient to failures of their dependencies. If you’re interested in helping solve these problems at scale, please visit cloudflare.com/careers.