Post Syndicated from Katharine Childs original https://www.raspberrypi.org/blog/using-e-textiles-to-deliver-equitable-computing-lessons-and-broaden-participation/

In our current series of research seminars, we are exploring how computing can be connected to other subjects using cross-disciplinary approaches. In July 2022, our speakers were Professor Yasmin Kafai from the University of Pennsylvania and Elaine Griggs, an award-winning teacher from Pembroke High School, Massachusetts, and we heard about their use of e-textiles to engage learners and broaden participation in computing.

Building new clubhouses

The spaces where young people learn about computing have sometimes been referred to as clubhouses to relate them to the places where sports or social clubs meet. A computing clubhouse can be a place where learners come together to take part in computing activities and gain a sense of community. However, as Yasmin pointed out, research has found that computing clubhouses have also often been dominated by electronics and robotics activities. This has led to clubhouses being perceived as exclusive spaces for only the young people who share those interests.

Yasmin’s work is motivated by the idea of building new clubhouses that include a wide range of computing interests, with a specific focus on spaces for e-textile activities, to show that diverse uses of computing are valued.

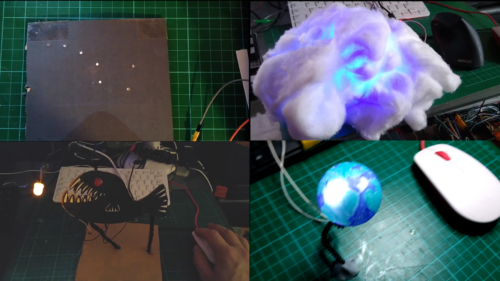

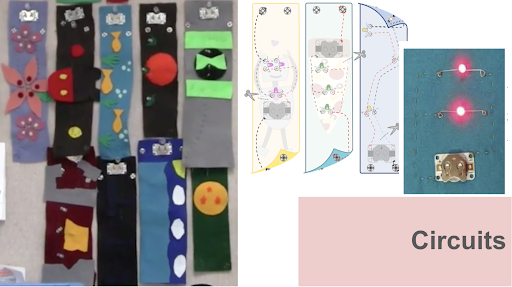

Yasmin’s research into learning through e-textiles has taken place in formal computing lessons in high schools in America, by developing and using a unit from the Exploring Computer Science curriculum called “Stitching the Loop”. In the seminar, we were fortunate to be joined by Elaine, a computer science and robotics teacher who has used the scheme of work in her classroom. Elaine’s learners have designed wearable electronic textile projects with microcontrollers, sensors, LEDs, and conductive thread. With these materials, learners have made items such as paper circuits, wristbands, and collaborative banners, as shown in the examples below.

Teaching approaches for equity-oriented learning

The hands-on, project-based approach in the e-textile unit has many similarities with the principles underpinning the work we do at the Raspberry Pi Foundation. However, there were also two specific teaching approaches that were embedded in Elaine’s teaching in order to promote equitable learning in the computing classroom:

- Prioritising time for learners to design their artefacts at the start of the activity.

- Reflecting on learning through the use of a digital portfolio.

Making time for design

As teachers with a set of learning outcomes to deliver, we can often feel a certain pressure to structure lessons so that our learners spend the most time on activities that we feel will deliver those outcomes. I was very interested to hear how in these e-textile projects, there was a deliberate choice to foreground the aesthetics. When learners spent time designing their artefacts and could link it to their own interests, they had a sense of personal ownership over what they were making, which encouraged them to persevere and overcome any difficulties with sewing, code, or electronics.

My personal reflection was that creating a digital textiles project based on a set template could be considered the equivalent of teaching programming by copying code. Both approaches would increase the chances of a successful output, but wouldn’t necessarily increase learners’ understanding of computing concepts, nor encourage learners to perceive computing as a subject where everyone belongs. I was inspired by the insights shared at the seminar about how prioritising design time can lead to more diverse representations of making.

Reflecting on learning using a digital portfolio

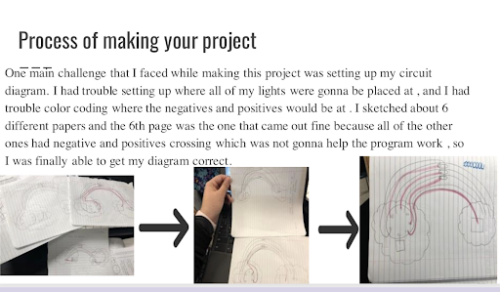

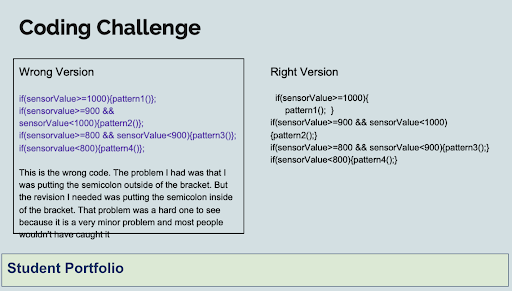

Elaine told us that learners were encouraged to create a digital portfolio which included photographs of the different stages of their project, examples of their code, and reflections on the problems that they had solved during the project. In the picture below, the learner has shared both the ‘wrong’ and ‘right’ versions of their code, along with an explanation of how they debugged the error.

Yasmin explained the equity-oriented theories underpinning the digital portfolio teaching approach. The learners’ reflections allowed deeper understanding of the computing and electronics concepts involved and helped to balance the personalised nature of their artefacts with the need to meet learning goals.

Yasmin also emphasised how important it was for learners to take part in a series of projects so that they encountered computing and electronics concepts more than once. In this way, reflective journalling can be seen as an equitable teaching approach because it helps to move learners on from their initial engagement into more complex projects. Thinking back to the clubhouse model, it is equally important for learners to be valued for their complex e-textile projects as it is for their complex robotics projects, and so portfolios of a series of e-textile projects show that a diverse range of learners can be successful in computing at the highest levels.

Try e-textiles with your learners

If you’re thinking about ways of introducing e-textile activities to your learners, there are some useful resources here:

- The Exploring Computer Science page contains all the information and resources relating to the “Stitching the Loop” electronic textiles unit. You can also find the video that Yasmin and Elaine shared during the seminar.

- For e-textiles in a non-formal learning space, the StitchFest webpage has lots of information about an e-textile hackathon that took place in 2014, designed to broaden participation and perceptions in computing.

- “3D LED science display with Scratch” is a project that combines using LEDs with science and nature to create a 3D installation. This project is from the Raspberry Pi Foundation’s “Physical computing with Scratch and the Raspberry Pi” projects pathway.

Looking forward to our next free seminar

We’re having a short break in the seminar series but will be back in September when we’ll be continuing to find out more about cross-disciplinary approaches to computing.

In our next seminar on Tuesday 6 September 2022 at 17:00–18:30 BST / 12:00–13:30 EST / 9:00–10:30 PST / 18:00–19:30 CEST, we’ll be hearing all about the links between computing and dance, with our speaker Genevieve Smith-Nunes (University of Cambridge). Genevieve will be speaking about data ethics for the computing classroom through biometrics, ballet, and augmented reality (AR) which promises to be a fascinating perspective on bringing computing to new audiences.

The post Using e-textiles to deliver equitable computing lessons and broaden participation appeared first on Raspberry Pi.