Post Syndicated from Vicky Fisher original https://www.raspberrypi.org/blog/global-impact-empowering-young-people-in-kenya-and-south-africa/

We work with mission-aligned educational organisations all over the world to support young people’s computing education. In 2023 we established four partnerships in Kenya and South Africa with organisations Coder:LevelUp, Blue Roof, Oasis Mathare, and Tech Kidz Africa, which support young people in underserved communities. Our shared goal is to support educators to establish and sustain extracurricular Code Clubs and CoderDojos in schools and community organisations. Here we share insights into the impact the partnerships are having.

Evaluating the impact of the training

In the partnerships we used a ‘train the trainer’ model, which focuses on equipping our partners with the knowledge and skills to train and support educators and learners. This meant that we trained a group of educators from each partner, enabling them to then run their own training sessions for other educators so they can set up coding clubs and run coding sessions. These coding sessions aim to increase young people’s skills and confidence in computing and programming.

We also conducted an evaluation of the impact of our work in these partnerships. We shared two surveys with educators (one shortly after they completed their initial training, a second for when they were running coding sessions), and another survey for young people to fill in during their coding sessions. In two of the partnerships, we also conducted interviews and focus groups with educators and young people.

Although we received lots of valuable feedback, only a low proportion of participants responded to our surveys, so the data may not be representative of the experience of all participating educators.

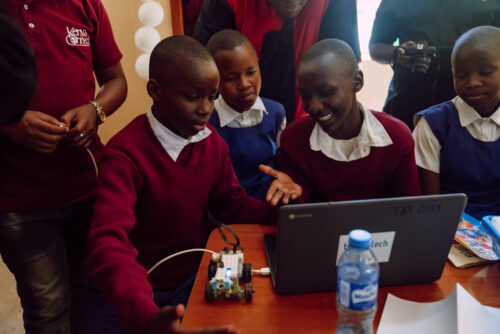

New opportunities to learn to code

Following our training, our partners themselves trained 332 educators across Kenya and South Africa to work directly in schools and communities running coding sessions. This led to the setup of nearly 250 Code Clubs and CoderDojos and additional coding sessions in schools and communities, reaching more than 11,500 young people.

As a result, access to coding and programming has increased in areas where this provision would otherwise not be available. One educator told us:

“We found it extremely beneficial, because a lot of our children come from areas in the community where they barely know how to read and write, let alone know how to use a computer… [It provides] the foundation, creating a fun way of approaching the computer as opposed to it being daunting.”

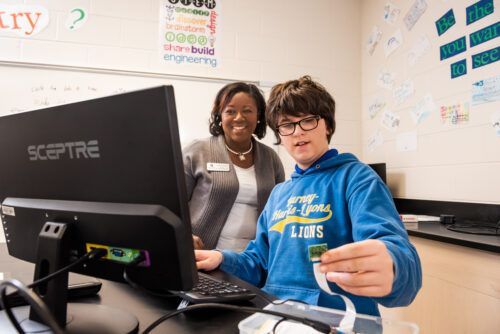

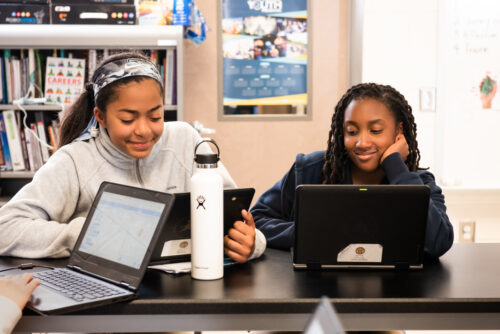

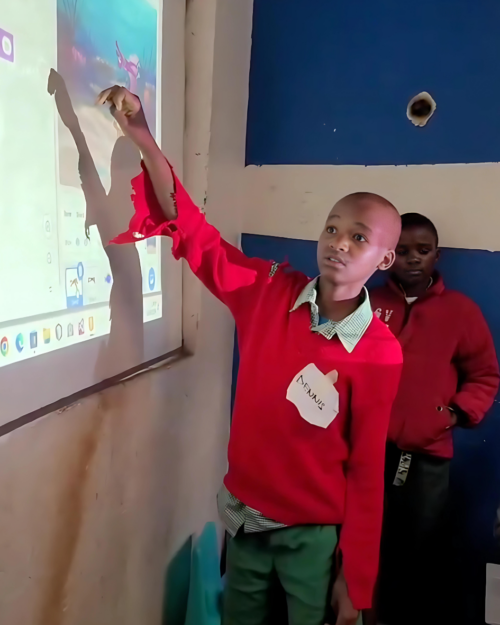

Curiosity, excitement and increased confidence

We found encouraging signs of the impact of this work on young people.

Nearly 90% of educators reported seeing an increase in young people’s computing skills, with over half of educators reporting that this increase was large. Over three quarters of young people who filled in our survey reported feeling confident in coding and computer programming.

The young people spoke enthusiastically about what they had learned and the programs they had created. They told us they felt inspired to keep learning, linking their interests to what they wanted to do in coding sessions. Interests included making dolls, games, cartoons, robots, cars, and stories.

When we spoke with educators and young people, a key theme that emerged was the enthusiasm and curiosity of the young people to learn more. Educators described how motivated they felt by the excitement of the young people. Young people particularly enjoyed finding out the role of programming in the world around them, from understanding traffic lights to knowing more about the games they play on their phones.

One educator told us:

“…students who knew nothing about technology are getting empowered.”

This confidence is particularly encouraging given that educators reported a low level of computer literacy among young people at the start of the coding sessions. One educator described how coding sessions provided an engaging hook to support teaching basic IT skills, such as mouse skills and computer-related terms, alongside coding.

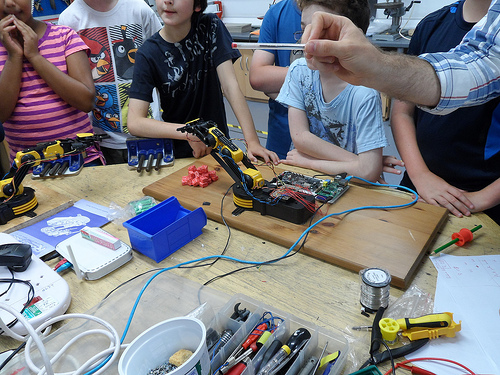

Addressing real-world problems

One educator gave an example of young people using what they are learning in their coding club to solve real-world problems, saying:

“It’s life-changing because some of those kids and the youths that you are teaching… they’re using them to automate things in their houses.”

Many of these young people live in informal settlements where there are frequent fires, and have started using skills they learned in the coding sessions to automate things in their homes, reducing the risk of fires. For example, they are programming a device that controls fans so that they switch on when the temperature gets too high, and ways to switch appliances such as light bulbs on and off by clapping.

Continuing to improve our support

From the gathered feedback, we also learned some useful lessons to help improve the quality of our offer and support to our partners. For example, educators faced challenges including lack of devices for young people, and low internet connectivity. As we continue to develop these partnerships, we will work with partners to make use of our unplugged activities that work offline, removing the barriers created by low connectivity.

We are continuing to develop the training we offer and making sure that educators are able to access our other training and resources. We are also using the feedback they have given us to consider where additional training and support may be needed. Future evaluations will further strengthen our evidence and provide us with the insights we need to continue developing our work and support more educators and young people.

Our thanks to our partners at Coder:LevelUp, Blue Roof, Oasis Mathare, and Tech Kidz Africa for sharing our mission to enable young people to realise their full potential through the power of computing and digital technologies. As we continue to build partnerships to support Code Clubs and CoderDojos across South Africa and Kenya, it is heartening to hear first-hand accounts of the positive impact this work has on young people.

If your organisation would like to partner with us to bring computing education to young people you support, please send us a message with the subject ‘Partnerships’.

The post Global Impact: Empowering young people in Kenya and South Africa appeared first on Raspberry Pi Foundation.