Post Syndicated from Katharine Childs original https://www.raspberrypi.org/blog/insights-into-students-attitudes-to-using-ai-tools-in-programming-education/

Educators around the world are grappling with the problem of whether to use artificial intelligence (AI) tools in the classroom. As more and more teachers start exploring the ways to use these tools for teaching and learning computing, there is an urgent need to understand the impact of their use to make sure they do not exacerbate the digital divide and leave some students behind.

Sri Yash Tadimalla from the University of North Carolina and Dr Mary Lou Maher, Director of Research Community Initiatives at the Computing Research Association, are exploring how student identities affect their interaction with AI tools and their perceptions of the use of AI tools. They presented findings from two of their research projects in our March seminar.

How students interact with AI tools

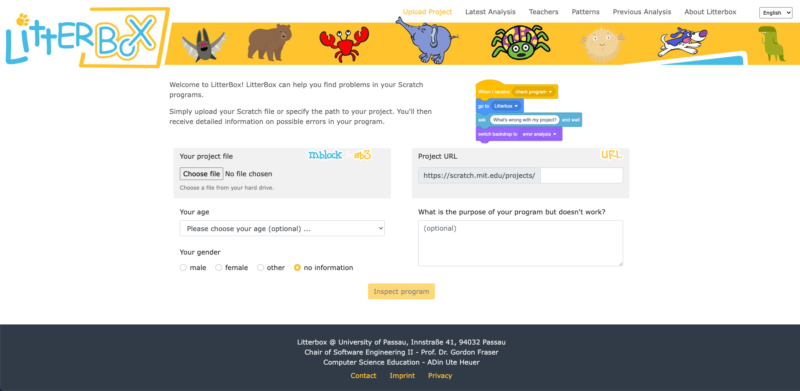

A common approach in research is to begin with a preliminary study involving a small group of participants in order to test a hypothesis, ways of collecting data from participants, and an intervention. Yash explained that this was the approach they took with a group of 25 undergraduate students on an introductory Java programming course. The research observed the students as they performed a set of programming tasks using an AI chatbot tool (ChatGPT) or an AI code generator tool (GitHub Copilot).

The data analysis uncovered five emergent attitudes of students using AI tools to complete programming tasks:

- Highly confident students rely heavily on AI tools and are confident about the quality of the code generated by the tool without verifying it

- Cautious students are careful in their use of AI tools and verify the accuracy of the code produced

- Curious students are interested in exploring the capabilities of the AI tool and are likely to experiment with different prompts

- Frustrated students struggle with using the AI tool to complete the task and are likely to give up

- Innovative students use the AI tool in creative ways, for example to generate code for other programming tasks

Whether these attitudes are common for other and larger groups of students requires more research. However, these preliminary groupings may be useful for educators who want to understand their students and how to support them with targeted instructional techniques. For example, highly confident students may need encouragement to check the accuracy of AI-generated code, while frustrated students may need assistance to use the AI tools to complete programming tasks.

An intersectional approach to investigating student attitudes

Yash and Mary Lou explained that their next research study took an intersectional approach to student identity. Intersectionality is a way of exploring identity using more than one defining characteristic, such as ethnicity and gender, or education and class. Intersectional approaches acknowledge that a person’s experiences are shaped by the combination of their identity characteristics, which can sometimes confer multiple privileges or lead to multiple disadvantages.

In the second research study, 50 undergraduate students participated in programming tasks and their approaches and attitudes were observed. The gathered data was analysed using intersectional groupings, such as:

- Students who were from the first generation in their family to attend university and female

- Students who were from an underrepresented ethnic group and female

Although the researchers observed differences amongst the groups of students, there was not enough data to determine whether these differences were statistically significant.

Who thinks using AI tools should be considered cheating?

Participating students were also asked about their views on using AI tools, such as “Did having AI help you in the process of programming?” and “Does your experience with using this AI tool motivate you to continue learning more about programming?”

The same intersectional approach was taken towards analysing students’ answers. One surprising finding stood out: when asked whether using AI tools to help with programming tasks should be considered cheating, students from more privileged backgrounds agreed that this was true, whilst students with less privilege disagreed and said it was not cheating.

This finding is only with a very small group of students at a single university, but Yash and Mary Lou called for other researchers to replicate this study with other groups of students to investigate further.

You can watch the full seminar here:

Acknowledging differences to prevent deepening divides

As researchers and educators, we often hear that we should educate students about the importance of making AI ethical, fair, and accessible to everyone. However, simply hearing this message isn’t the same as truly believing it. If students’ identities influence how they view the use of AI tools, it could affect how they engage with these tools for learning. Without recognising these differences, we risk continuing to create wider and deeper digital divides.

Join our next seminar

The focus of our ongoing seminar series is on teaching programming with or without AI.

For our next seminar on Tuesday 16 April at 17:00 to 18:30 GMT, we’re joined by Brett A. Becker (University College Dublin), who will talk about how generative AI can be used effectively in secondary school programming education and how it can be leveraged so that students can be best prepared for continuing their education or beginning their careers. To take part in the seminar, click the button below to sign up, and we will send you information about how to join. We hope to see you there.

The schedule of our upcoming seminars is online. You can catch up on past seminars on our blog and on the previous seminars and recordings page.

The post Insights into students’ attitudes to using AI tools in programming education appeared first on Raspberry Pi Foundation.