Post Syndicated from Sue Sentance original https://www.raspberrypi.org/blog/research-seminar-formative-assessment-computer-science-classroom/

In computing education research, considerable focus has been put on the design of teaching materials and learning resources, and investigating how young people learn computing concepts. But there has been less focus on assessment, particularly assessment for learning, which is called formative assessment. As classroom teachers are engaged in assessment activities all the time, it’s pretty strange that researchers in the area of computing and computer science in school have not put a lot of focus on this.

That’s why in our most recent seminar, we were delighted to hear about formative assessment — assessment for learning — from Dr Shuchi Grover, of Looking Glass Ventures and Stanford University in the USA. Shuchi has a long track record of work in the learning sciences (called education research in the UK), and her contribution in the area of computational thinking has been hugely influential and widely drawn on in subsequent research.

Two types of assessment

Assessment is typically divided into two types:

- Summative assessment (i.e. assessing what has been learned), which typically takes place through examinations, final coursework, projects, etcetera.

- Formative assessment (i.e. assessment for learning), which is not aimed at giving grades and typically takes place through questioning, observation, plenary classroom activities, and dialogue with students.

Through formative assessment, teachers seek to find out where students are at, in order to use that information both to direct their preparation for the next teaching activities and to give students useful feedback to help them progress. Formative assessment can be used to surface misconceptions (or alternate conceptions) and for diagnosis of student difficulties.

As Shuchi outlined in her talk, a variety of activities can be used for formative assessment, for example:

- Self- and peer-assessment activities (commonly used in schools).

- Different forms of questioning and quizzes to support learning (not graded tests).

- Rubrics and self-explanations (for assessing projects).

A framework for formative assessment

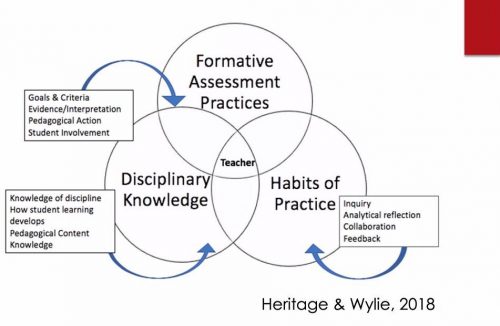

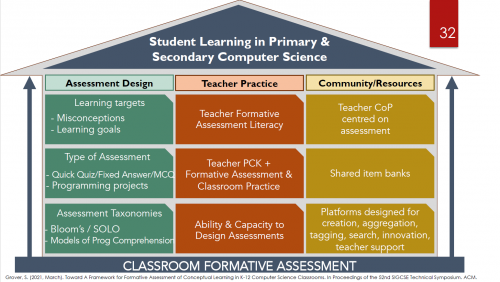

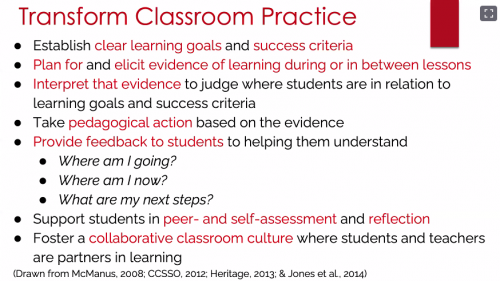

Shuchi described her own research in this topic, including a framework she has developed for formative assessment. This comprises three pillars:

- Assessment design.

- Teacher or classroom practice.

- The role of the community in furthering assessment practice.

Shuchi’s presentation then focused on part of the first pillar in the framework: types of assessments, and particularly types of multiple-choice questions that can be automatically marked or graded using software tools. Tools obviously don’t replace teachers, but they can be really useful for providing timely and short-turnaround feedback for students.

As part of formative assessment, carefully chosen questions can also be used to reveal students’ misconceptions about the subject matter — these are called diagnostic questions. Shuchi discussed how in a classroom setting, teachers can employ this kind of question to help them decide what to focus on in future lessons, and to understand their students’ alternate or different conceptions of a topic.

Formative assessment of programming skills

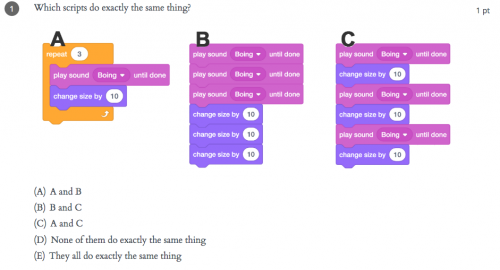

The remainder of the seminar focused on the formative assessment of programming skills. There are many ways of assessing developing programming skills (see Shuchi’s slides), including Parsons problems, microworlds, hotspot items, rubrics (for artifacts), and multiple-choice questions. As an MCQ example, in the figure below you can see some snippets of block-based code, which students need to read and work out what the outcome of running the snippets will be.

Questions such as this highlight that it’s important for learners to engage in code comprehension and code reading activities when learning to program. This really underlines the fact that such assessment exercises can be used to support learning just as much as to monitor progress.

Formative assessment: our support for teachers

Interestingly, Shuchi commented that in her experience, teachers in the UK are more used to using code reading activities than US teachers. This may be because code comprehension activities are embedded into the curriculum materials and support for pedagogy, both of which the Raspberry Pi Foundation developed as part of the National Centre for Computing Education in England. We explicitly share approaches to teaching programming that incorporate code reading, for example the PRIMM approach. Moreover, our work in the Raspberry Pi Foundation includes the Isaac Computer Science online learning platform for A level computer science students and teachers, which is centered around different types of questions designed as tools for learning.

All these materials are freely available to teachers wherever they are based.

Further work on formative assessment

Based on her work in US classrooms researching this topic, Shuchi’s call to action for teachers was to pay attention to formative assessment in computer science classrooms and to investigate what useful tools can support them to give feedback to students about their learning.

Shuchi is currently involved in an NSF-funded research project called CS Assess to further develop formative assessment in computer science via a community of educators. For further reading, there are two chapters related to formative assessment in computer science classrooms in the recently published book Computer Science in K-12 edited by Shuchi.

There was much to take away from this seminar, and we are really grateful to Shuchi for her input and look forward to hearing more about her developing project.

Join our next seminar

If you missed the seminar, you can find the presentation slides and a recording of the Shuchi’s talk on our seminars page.

In our next seminar on Tuesday 3 November at 17:00–18:30 BST / 12:00–13:30 EDT / 9:00–10:30 PT / 18:00–19:30 CEST, I will be presenting my work on PRIMM, particularly focusing on language and talk in programming lessons. To join, simply sign up with your name and email address.

Once you’ve signed up, we’ll email you the seminar meeting link and instructions for joining. If you attended this past seminar, the link remains the same.

The post Formative assessment in the computer science classroom appeared first on Raspberry Pi.