Post Syndicated from Ignat Korchagin original https://blog.cloudflare.com/how-to-execute-an-object-file-part-3/

Dealing with external libraries

In the part 2 of our series we learned how to process relocations in object files in order to properly wire up internal dependencies in the code. In this post we will look into what happens if the code has external dependencies — that is, it tries to call functions from external libraries. As before, we will be building upon the code from part 2. Let’s add another function to our toy object file:

obj.c:

#include <stdio.h>

...

void say_hello(void)

{

puts("Hello, world!");

}

In the above scenario our say_hello function now depends on the puts function from the C standard library. To try it out we also need to modify our loader to import the new function and execute it:

loader.c:

...

static void execute_funcs(void)

{

/* pointers to imported functions */

int (*add5)(int);

int (*add10)(int);

const char *(*get_hello)(void);

int (*get_var)(void);

void (*set_var)(int num);

void (*say_hello)(void);

...

say_hello = lookup_function("say_hello");

if (!say_hello) {

fputs("Failed to find say_hello function\n", stderr);

exit(ENOENT);

}

puts("Executing say_hello...");

say_hello();

}

...

Let’s run it:

$ gcc -c obj.c

$ gcc -o loader loader.c

$ ./loader

No runtime base address for section

Seems something went wrong when the loader tried to process relocations, so let’s check the relocations table:

$ readelf --relocs obj.o

Relocation section '.rela.text' at offset 0x3c8 contains 7 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

000000000020 000a00000004 R_X86_64_PLT32 0000000000000000 add5 - 4

00000000002d 000a00000004 R_X86_64_PLT32 0000000000000000 add5 - 4

00000000003a 000500000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .rodata - 4

000000000046 000300000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .data - 4

000000000058 000300000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .data - 4

000000000066 000500000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .rodata - 4

00000000006b 001100000004 R_X86_64_PLT32 0000000000000000 puts - 4

...

The compiler generated a relocation for the puts invocation. The relocation type is R_X86_64_PLT32 and our loader already knows how to process these, so the problem is elsewhere. The above entry shows that the relocation references 17th entry (0x11 in hex) in the symbol table, so let’s check that:

$ readelf --symbols obj.o

Symbol table '.symtab' contains 18 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 0000000000000000 0 FILE LOCAL DEFAULT ABS obj.c

2: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 1

3: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 3

4: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 4

5: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 5

6: 0000000000000000 4 OBJECT LOCAL DEFAULT 3 var

7: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 7

8: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 8

9: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 6

10: 0000000000000000 15 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 add5

11: 000000000000000f 36 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 add10

12: 0000000000000033 13 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 get_hello

13: 0000000000000040 12 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 get_var

14: 000000000000004c 19 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 set_var

15: 000000000000005f 19 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 say_hello

16: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT UND _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_

17: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT UND puts

Oh! The section index for the puts function is UND (essentially 0 in the code), which makes total sense: unlike previous symbols, puts is an external dependency, and it is not implemented in our obj.o file. Therefore, it can’t be a part of any section within obj.o.

So how do we resolve this relocation? We need to somehow point the code to jump to a puts implementation. Our loader actually already has access to the C library puts function (because it is written in C and we’ve used puts in the loader code itself already), but technically it doesn’t have to be the C library puts, just some puts implementation. For completeness, let’s implement our own custom puts function in the loader, which is just a decorator around the C library puts:

loader.c:

...

/* external dependencies for obj.o */

static int my_puts(const char *s)

{

puts("my_puts executed");

return puts(s);

}

...

Now that we have a puts implementation (and thus its runtime address) we should just write logic in the loader to resolve the relocation by instructing the code to jump to the correct function. However, there is one complication: in part 2 of our series, when we processed relocations for constants and global variables, we learned we’re mostly dealing with 32-bit relative relocations and that the code or data we’re referencing needs to be no more than 2147483647 (0x7fffffff in hex) bytes away from the relocation itself. R_X86_64_PLT32 is also a 32-bit relative relocation, so it has the same requirements, but unfortunately we can’t reuse the trick from part 2 as our my_puts function is part of the loader itself and we don’t have control over where in the address space the operating system places the loader code.

Luckily, we don’t have to come up with any new solutions and can just borrow the approach used in shared libraries.

Exploring PLT/GOT

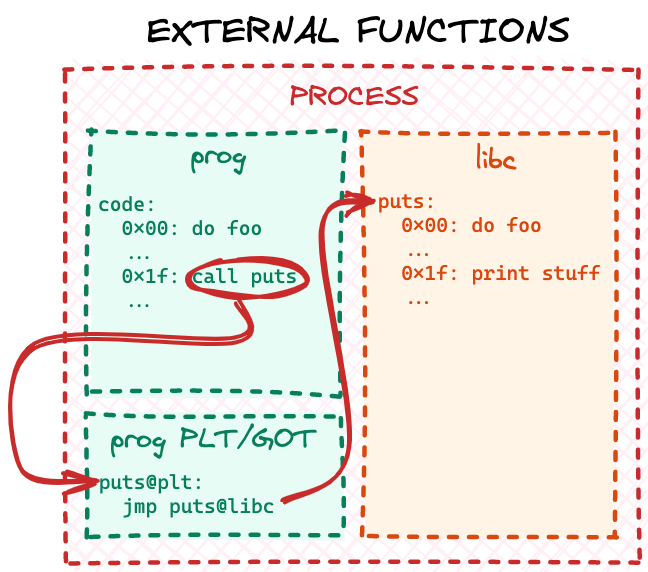

Real world ELF executables and shared libraries have the same problem: often executables have dependencies on shared libraries and shared libraries have dependencies on other shared libraries. And all of the different pieces of a complete runtime program may be mapped to random ranges in the process address space. When a shared library or an ELF executable is linked together, the linker enumerates all the external references and creates two or more additional sections (for a refresher on ELF sections check out the part 1 of our series) in the ELF file. The two mandatory ones are the Procedure Linkage Table (PLT) and the Global Offset Table (GOT).

We will not deep-dive into specifics of the standard PLT/GOT implementation as there are many other great resources online, but in a nutshell PLT/GOT is just a jumptable for external code. At the linking stage the linker resolves all external 32-bit relative relocations with respect to a locally generated PLT/GOT table. It can do that, because this table would become part of the final ELF file itself, so it will be "close" to the main code, when the file is mapped into memory at runtime. Later, at runtime the dynamic loader populates PLT/GOT tables for every loaded ELF file (both the executable and the shared libraries) with the runtime addresses of all the dependencies. Eventually, when the program code calls some external library function, the CPU "jumps" through the local PLT/GOT table to the final code:

Why do we need two ELF sections to implement one jumptable you may ask? Well, because real world PLT/GOT is a bit more complex than described above. Turns out resolving all external references at runtime may significantly slow down program startup time, so symbol resolution is implemented via a "lazy approach": a reference is resolved by the dynamic loader only when the code actually tries to call a particular function. If the main application code never calls a library function, that reference will never be resolved.

Implementing a simplified PLT/GOT

For learning and demonstrative purposes though we will not be reimplementing a full-blown PLT/GOT with lazy resolution, but a simple jumptable, which resolves external references when the object file is loaded and parsed. First of all we need to know the size of the table: for ELF executables and shared libraries the linker will count the external references at link stage and create appropriately sized PLT and GOT sections. Because we are dealing with raw object files we would have to do another pass over the .rela.text section and count all the relocations, which point to an entry in the symbol table with undefined section index (or 0 in code). Let’s add a function for this and store the number of external references in a global variable:

loader.c:

...

/* number of external symbols in the symbol table */

static int num_ext_symbols = 0;

...

static void count_external_symbols(void)

{

const Elf64_Shdr *rela_text_hdr = lookup_section(".rela.text");

if (!rela_text_hdr) {

fputs("Failed to find .rela.text\n", stderr);

exit(ENOEXEC);

}

int num_relocations = rela_text_hdr->sh_size / rela_text_hdr->sh_entsize;

const Elf64_Rela *relocations = (Elf64_Rela *)(obj.base + rela_text_hdr->sh_offset);

for (int i = 0; i < num_relocations; i++) {

int symbol_idx = ELF64_R_SYM(relocations[i].r_info);

/* if there is no section associated with a symbol, it is probably

* an external reference */

if (symbols[symbol_idx].st_shndx == SHN_UNDEF)

num_ext_symbols++;

}

}

...

This function is very similar to our do_text_relocations function. Only instead of actually performing relocations it just counts the number of external symbol references.

Next we need to decide the actual size in bytes for our jumptable. num_ext_symbols has the number of external symbol references in the object file, but how many bytes per symbol to allocate? To figure this out we need to design our jumptable format. As we established above, in its simple form our jumptable should be just a collection of unconditional CPU jump instructions — one for each external symbol. However, unfortunately modern x64 CPU architecture does not provide a jump instruction, where an address pointer can be a direct operand. Instead, the jump address needs to be stored in memory somewhere "close" — that is within 32-bit offset — and the offset is the actual operand. So, for each external symbol we need to store the jump address (64 bits or 8 bytes on a 64-bit CPU system) and the actual jump instruction with an offset operand (6 bytes for x64 architecture). We can represent an entry in our jumptable with the following C structure:

loader.c:

...

struct ext_jump {

/* address to jump to */

uint8_t *addr;

/* unconditional x64 JMP instruction */

/* should always be {0xff, 0x25, 0xf2, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff} */

/* so it would jump to an address stored at addr above */

uint8_t instr[6];

};

struct ext_jump *jumptable;

...

We’ve also added a global variable to store the base address of the jumptable, which will be allocated later. Notice that with the above approach the actual jump instruction will always be constant for every external symbol. Since we allocate a dedicated entry for each external symbol with this structure, the addr member would always be at the same offset from the end of the jump instruction in instr: -14 bytes or 0xfffffff2 in hex for a 32-bit operand. So instr will always be {0xff, 0x25, 0xf2, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff}: 0xff and 0x25 is the encoding of the x64 jump instruction and its modifier and 0xfffffff2 is the operand offset in little-endian format.

Now that we have defined the entry format for our jumptable, we can allocate and populate it when parsing the object file. First of all, let’s not forget to call our new count_external_symbols function from the parse_obj to populate num_ext_symbols (it has to be done before we allocate the jumptable):

loader.c:

...

static void parse_obj(void)

{

...

count_external_symbols();

/* allocate memory for `.text`, `.data` and `.rodata` copies rounding up each section to whole pages */

text_runtime_base = mmap(NULL, page_align(text_hdr->sh_size)...

...

}

Next we need to allocate memory for the jumptable and store the pointer in the jumptable global variable for later use. Just a reminder that in order to resolve 32-bit relocations from the .text section to this table, it has to be "close" in memory to the main code. So we need to allocate it in the same mmap call as the rest of the object sections. Since we defined the table’s entry format in struct ext_jump and have num_ext_symbols, the size of the table would simply be sizeof(struct ext_jump) * num_ext_symbols:

loader.c:

...

static void parse_obj(void)

{

...

count_external_symbols();

/* allocate memory for `.text`, `.data` and `.rodata` copies and the jumptable for external symbols, rounding up each section to whole pages */

text_runtime_base = mmap(NULL, page_align(text_hdr->sh_size) + \

page_align(data_hdr->sh_size) + \

page_align(rodata_hdr->sh_size) + \

page_align(sizeof(struct ext_jump) * num_ext_symbols),

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

if (text_runtime_base == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("Failed to allocate memory");

exit(errno);

}

...

rodata_runtime_base = data_runtime_base + page_align(data_hdr->sh_size);

/* jumptable will come after .rodata */

jumptable = (struct ext_jump *)(rodata_runtime_base + page_align(rodata_hdr->sh_size));

...

}

...

Finally, because the CPU will actually be executing the jump instructions from our instr fields from the jumptable, we need to mark this memory readonly and executable (after do_text_relocations earlier in this function has completed):

loader.c:

...

static void parse_obj(void)

{

...

do_text_relocations();

...

/* make the jumptable readonly and executable */

if (mprotect(jumptable, page_align(sizeof(struct ext_jump) * num_ext_symbols), PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC)) {

perror("Failed to make the jumptable executable");

exit(errno);

}

}

...

At this stage we have our jumptable allocated and usable — all is left to do is to populate it properly. We’ll do this by improving the do_text_relocations implementation to handle the case of external symbols. The No runtime base address for section error from the beginning of this post is actually caused by this line in do_text_relocations:

loader.c:

...

static void do_text_relocations(void)

{

...

for (int i = 0; i < num_relocations; i++) {

...

/* symbol, with respect to which the relocation is performed */

uint8_t *symbol_address = = section_runtime_base(§ions[symbols[symbol_idx].st_shndx]) + symbols[symbol_idx].st_value;

...

}

...

Currently we try to determine the runtime symbol address for the relocation by looking up the symbol’s section runtime address and adding the symbol’s offset. But we have established above that external symbols do not have an associated section, so their handling needs to be a special case. Let’s update the implementation to reflect this:

loader.c:

...

static void do_text_relocations(void)

{

...

for (int i = 0; i < num_relocations; i++) {

...

/* symbol, with respect to which the relocation is performed */

uint8_t *symbol_address;

/* if this is an external symbol */

if (symbols[symbol_idx].st_shndx == SHN_UNDEF) {

static int curr_jmp_idx = 0;

/* get external symbol/function address by name */

jumptable[curr_jmp_idx].addr = lookup_ext_function(strtab + symbols[symbol_idx].st_name);

/* x64 unconditional JMP with address stored at -14 bytes offset */

/* will use the address stored in addr above */

jumptable[curr_jmp_idx].instr[0] = 0xff;

jumptable[curr_jmp_idx].instr[1] = 0x25;

jumptable[curr_jmp_idx].instr[2] = 0xf2;

jumptable[curr_jmp_idx].instr[3] = 0xff;

jumptable[curr_jmp_idx].instr[4] = 0xff;

jumptable[curr_jmp_idx].instr[5] = 0xff;

/* resolve the relocation with respect to this unconditional JMP */

symbol_address = (uint8_t *)(&jumptable[curr_jmp_idx].instr);

curr_jmp_idx++;

} else {

symbol_address = section_runtime_base(§ions[symbols[symbol_idx].st_shndx]) + symbols[symbol_idx].st_value;

}

...

}

...

If a relocation symbol does not have an associated section, we consider it external and call a helper function to lookup the symbol’s runtime address by its name. We store this address in the next available jumptable entry, populate the x64 jump instruction with our fixed operand and store the address of the instruction in the symbol_address variable. Later, the existing code in do_text_relocations will resolve the .text relocation with respect to the address in symbol_address in the same way it does for local symbols in part 2 of our series.

The only missing bit here now is the implementation of the newly introduced lookup_ext_function helper. Real world loaders may have complicated logic on how to find and resolve symbols in memory at runtime. But for the purposes of this article we’ll provide a simple naive implementation, which can only resolve the puts function:

loader.c:

...

static void *lookup_ext_function(const char *name)

{

size_t name_len = strlen(name);

if (name_len == strlen("puts") && !strcmp(name, "puts"))

return my_puts;

fprintf(stderr, "No address for function %s\n", name);

exit(ENOENT);

}

...

Notice though that because we control the loader logic we are free to implement resolution as we please. In the above case we actually "divert" the object file to use our own "custom" my_puts function instead of the C library one. Let’s recompile the loader and see if it works:

$ gcc -o loader loader.c

$ ./loader

Executing add5...

add5(42) = 47

Executing add10...

add10(42) = 52

Executing get_hello...

get_hello() = Hello, world!

Executing get_var...

get_var() = 5

Executing set_var(42)...

Executing get_var again...

get_var() = 42

Executing say_hello...

my_puts executed

Hello, world!

Hooray! We not only fixed our loader to handle external references in object files — we have also learned how to "hook" any such external function call and divert the code to a custom implementation, which might be useful in some cases, like malware research.

As in the previous posts, the complete source code from this post is available on GitHub.