Post Syndicated from Alissa Starzak original https://blog.cloudflare.com/consequences-of-ip-blocking/

In late August 2022, Cloudflare’s customer support team began to receive complaints about sites on our network being down in Austria. Our team immediately went into action to try to identify the source of what looked from the outside like a partial Internet outage in Austria. We quickly realized that it was an issue with local Austrian Internet Service Providers.

But the service disruption wasn’t the result of a technical problem. As we later learned from media reports, what we were seeing was the result of a court order. Without any notice to Cloudflare, an Austrian court had ordered Austrian Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to block 11 of Cloudflare’s IP addresses.

In an attempt to block 14 websites that copyright holders argued were violating copyright, the court-ordered IP block rendered thousands of websites inaccessible to ordinary Internet users in Austria over a two-day period. What did the thousands of other sites do wrong? Nothing. They were a temporary casualty of the failure to build legal remedies and systems that reflect the Internet’s actual architecture.

Today, we are going to dive into a discussion of IP blocking: why we see it, what it is, what it does, who it affects, and why it’s such a problematic way to address content online.

Collateral effects, large and small

The craziest thing is that this type of blocking happens on a regular basis, all around the world. But unless that blocking happens at the scale of what happened in Austria, or someone decides to highlight it, it is typically invisible to the outside world. Even Cloudflare, with deep technical expertise and understanding about how blocking works, can’t routinely see when an IP address is blocked.

For Internet users, it’s even more opaque. They generally don’t know why they can’t connect to a particular website, where the connection problem is coming from, or how to address it. They simply know they cannot access the site they were trying to visit. And that can make it challenging to document when sites have become inaccessible because of IP address blocking.

Blocking practices are also wide-spread. In their Freedom on the Net report, Freedom House recently reported that 40 out of the 70 countries that they examined – which vary from countries like Russia, Iran and Egypt to Western democracies like the United Kingdom and Germany – did some form of website blocking. Although the report doesn’t delve into exactly how those countries block, many of them use forms of IP blocking, with the same kind of potential effects for a partial Internet shutdown that we saw in Austria.

Although it can be challenging to assess the amount of collateral damage from IP blocking, we do have examples where organizations have attempted to quantify it. In conjunction with a case before the European Court of Human Rights, the European Information Society Institute, a Slovakia-based nonprofit, reviewed Russia’s regime for website blocking in 2017. Russia exclusively used IP addresses to block content. The European Information Society Institute concluded that IP blocking led to “collateral website blocking on a massive scale” and noted that as of June 28, 2017, “6,522,629 Internet resources had been blocked in Russia, of which 6,335,850 – or 97% – had been blocked collaterally, that is to say, without legal justification.”

In the UK, overbroad blocking prompted the non-profit Open Rights Group to create the website Blocked.org.uk. The website has a tool enabling users and site owners to report on overblocking and request that ISPs remove blocks. The group also has hundreds of individual stories about the effect of blocking on those whose websites were inappropriately blocked, from charities to small business owners. Although it’s not always clear what blocking methods are being used, the fact that the site is necessary at all conveys the amount of overblocking. Imagine a dressmaker, watchmaker or car dealer looking to advertise their services and potentially gain new customers with their website. That doesn’t work if local users can’t access the site.

One reaction might be, “Well, just make sure there are no restricted sites sharing an address with unrestricted sites.” But as we’ll discuss in more detail, this ignores the large difference between the number of possible domain names and the number of available IP addresses, and runs counter to the very technical specifications that empower the Internet. Moreover, the definitions of restricted and unrestricted differ across nations, communities, and organizations. Even if it were possible to know all the restrictions, the designs of the protocols — of the Internet, itself — mean that it is simply infeasible, if not impossible, to satisfy every agency’s constraints.

Legal and human rights concerns

Overblocking websites is not only a problem for users; it has legal implications. Because of the effect it can have on ordinary citizens looking to exercise their rights online, government entities (both courts and regulatory bodies) have a legal obligation to make sure that their orders are necessary and proportionate, and don’t unnecessarily affect those who are not contributing to the harm.

It would be hard to imagine, for example, that a court in response to alleged wrongdoing would blindly issue a search warrant or an order based solely on a street address without caring if that address was for a single family home, a six-unit condo building, or a high rise with hundreds of separate units. But those sorts of practices with IP addresses appear to be rampant.

In 2020, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) – the court overseeing the implementation of the Council of Europe’s European Convention on Human Rights – considered a case involving a website that was blocked in Russia not because it had been targeted by the Russian government, but because it shared an IP address with a blocked website. The website owner brought suit over the block. The ECHR concluded that the indiscriminate blocking was impermissible, ruling that the block on the lawful content of the site “amounts to arbitrary interference with the rights of owners of such websites.” In other words, the ECHR ruled that it was improper for a government to issue orders that resulted in the blocking of sites that were not targeted.

Using Internet infrastructure to address content challenges

Ordinary Internet users don’t think a lot about how the content they are trying to access online is delivered to them. They assume that when they type a domain name into their browser, the content will automatically pop up. And if it doesn’t, they tend to assume the website itself is having problems unless their entire Internet connection seems to be broken. But those basic assumptions ignore the reality that connections to a website are often used to limit access to content online.

Why do countries block connections to websites? Maybe they want to limit their own citizens from accessing what they believe to be illegal content – like online gambling or explicit material – that is permissible elsewhere in the world. Maybe they want to prevent the viewing of a foreign news source that they believe to be primarily disinformation. Or maybe they want to support copyright holders seeking to block access to a website to limit viewing of content that they believe infringes their intellectual property.

To be clear, blocking access is not the same thing as removing content from the Internet. There are a variety of legal obligations and authorities designed to permit actual removal of illegal content. Indeed, the legal expectation in many countries is that blocking is a matter of last resort, after attempts have been made to remove content at the source.

Blocking just prevents certain viewers – those whose Internet access depends on the ISP that is doing the blocking – from being able to access websites. The site itself continues to exist online and is accessible by everyone else. But when the content originates from a different place and can’t be easily removed, a country may see blocking as their best or only approach.

We recognize the concerns that sometimes drive countries to implement blocking. But fundamentally, we believe it’s important for users to know when the websites they are trying to access have been blocked, and, to the extent possible, who has blocked them from view and why. And it’s critical that any restrictions on content should be as limited as possible to address the harm, to avoid infringing on the rights of others.

Brute force IP address blocking doesn’t allow for those things. It’s fully opaque to Internet users. The practice has unintended, unavoidable consequences on other content. And the very fabric of the Internet means that there is no good way to identify what other websites might be affected either before or during an IP block.

To understand what happened in Austria and what happens in many other countries around the world that seek to block content with the bluntness of IP addresses, we have to understand what is going on behind the scenes. That means diving into some technical details.

Identity is attached to names, never addresses

Before we even get started describing the technical realities of blocking, it’s important to stress that the first and best option to deal with content is at the source. A website owner or hosting provider has the option of removing content at a granular level, without having to take down an entire website. On the more technical side, a domain name registrar or registry can potentially withdraw a domain name, and therefore a website, from the Internet altogether.

But how do you block access to a website, if for whatever reason the content owner or content source is unable or unwilling to remove it from the Internet? There are only three possible control points.

The first is via the Domain Name System (DNS), which translates domain names into IP addresses so that the site can be found. Instead of returning a valid IP address for a domain name, the DNS resolver could lie and respond with a code, NXDOMAIN, meaning that “there is no such name.” A better approach would be to use one of the honest error numbers standardized in 2020, including error 15 for blocked, error 16 for censored, 17 for filtered, or 18 for prohibited, although these are not widely used currently.

Interestingly, the precision and effectiveness of DNS as a control point depends on whether the DNS resolver is private or public. Private or ‘internal’ DNS resolvers are operated by ISPs and enterprise environments for their own known clients, which means that operators can be precise in applying content restrictions. By contrast, that level of precision is unavailable to open or public resolvers, not least because routing and addressing is global and ever-changing on the Internet map, and in stark contrast to addresses and routes on a fixed postal or street map. For example, private DNS resolvers may be able to block access to websites within specified geographic regions with at least some level of accuracy in a way that public DNS resolvers cannot, which becomes profoundly important given the disparate (and inconsistent) blocking regimes around the world.

The second approach is to block individual connection requests to a restricted domain name. When a user or client wants to visit a website, a connection is initiated from the client to a server name, i.e. the domain name. If a network or on-path device is able to observe the server name, then the connection can be terminated. Unlike DNS, there is no mechanism to communicate to the user that access to the server name was blocked, or why.

The third approach is to block access to an IP address where the domain name can be found. This is a bit like blocking the delivery of all mail to a physical address. Consider, for example, if that address is a skyscraper with its many unrelated and independent occupants. Halting delivery of mail to the address of the skyscraper causes collateral damage by invariably affecting all parties at that address. IP addresses work the same way.

Notably, the IP address is the only one of the three options that has no attachment to the domain name. The website domain name is not required for routing and delivery of data packets; in fact it is fully ignored. A website can be available on any IP address, or even on many IP addresses, simultaneously. And the set of IP addresses that a website is on can change at any time. The set of IP addresses cannot definitively be known by querying DNS, which has been able to return any valid address at any time for any reason, since 1995.

The idea that an address is representative of an identity is anathema to the Internet’s design, because the decoupling of address from name is deeply embedded in the Internet standards and protocols, as is explained next.

The Internet is a set of protocols, not a policy or perspective

Many people still incorrectly assume that an IP address represents a single website. We’ve previously stated that the association between names and addresses is understandable given that the earliest connected components of the Internet appeared as one computer, one interface, one address, and one name. This one-to-one association was an artifact of the ecosystem in which the Internet Protocol was deployed, and satisfied the needs of the time.

Despite the one-to-one naming practice of the early Internet, it has always been possible to assign more than one name to a server (or ‘host’). For example, a server was (and is still) often configured with names to reflect its service offerings such as mail.example.com and www.example.com, but these shared a base domain name. There were few reasons to have completely different domain names until the need to colocate completely different websites onto a single server. That practice was made easier in 1997 by the Host header in HTTP/1.1, a feature preserved by the SNI field in a TLS extension in 2003.

Throughout these changes, the Internet Protocol and, separately, the DNS protocol, have not only kept pace, but have remained fundamentally unchanged. They are the very reason that the Internet has been able to scale and evolve, because they are about addresses, reachability, and arbitrary name to IP address relationships.

The designs of IP and DNS are also entirely independent, which only reinforces that names are separate from addresses. A closer inspection of the protocols’ design elements illuminates the misperceptions of policies that lead to today’s common practice of controlling access to content by blocking IP addresses.

By design, IP is for reachability and nothing else

Much like large public civil engineering projects rely on building codes and best practice, the Internet is built using a set of open standards and specifications informed by experience and agreed by international consensus. The Internet standards that connect hardware and applications are published by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) in the form of “Requests for Comment” or RFCs — so named not to suggest incompleteness, but to reflect that standards must be able to evolve with knowledge and experience. The IETF and its RFCs are cemented in the very fabric of communications, for example, with the first RFC 1 published in 1969. The Internet Protocol (IP) specification reached RFC status in 1981.

Alongside the standards organizations, the Internet’s success has been helped by a core idea known as the end-to-end (e2e) principle, codified also in 1981, based on years of trial and error experience. The end-to-end principle is a powerful abstraction that, despite taking many forms, manifests a core notion of the Internet Protocol specification: the network’s only responsibility is to establish reachability, and every other possible feature has a cost or a risk.

The idea of “reachability” in the Internet Protocol is also enshrined in the design of IP addresses themselves. Looking at the Internet Protocol specification, RFC 791, the following excerpt from Section 2.3 is explicit about IP addresses having no association with names, interfaces, or anything else.

Addressing

A distinction is made between names, addresses, and routes [4]. A

name indicates what we seek. An address indicates where it is. A

route indicates how to get there. The internet protocol deals

primarily with addresses. It is the task of higher level (i.e.,

host-to-host or application) protocols to make the mapping from

names to addresses. The internet module maps internet addresses to

local net addresses. It is the task of lower level (i.e., local net

or gateways) procedures to make the mapping from local net addresses

to routes.

[ RFC 791, 1981 ]

Just like postal addresses for skyscrapers in the physical world, IP addresses are no more than street addresses written on a piece of paper. And just like a street address on paper, one can never be confident about the entities or organizations that exist behind an IP address. In a network like Cloudflare’s, any single IP address represents thousands of servers, and can have even more websites and services — in some cases numbering into the millions — expressly because the Internet Protocol is designed to enable it.

Here’s an interesting question: could we, or any content service provider, ensure that every IP address matches to one and only one name? The answer is an unequivocal no, and here too, because of a protocol design — in this case, DNS.

The number of names in DNS always exceeds the available addresses

A one-to-one relationship between names and addresses is impossible given the Internet specifications for the same reasons that it is infeasible in the physical world. Ignore for a moment that people and organizations can change addresses. Fundamentally, the number of people and organizations on the planet exceeds the number of postal addresses. We not only want, but need for the Internet to accommodate more names than addresses.

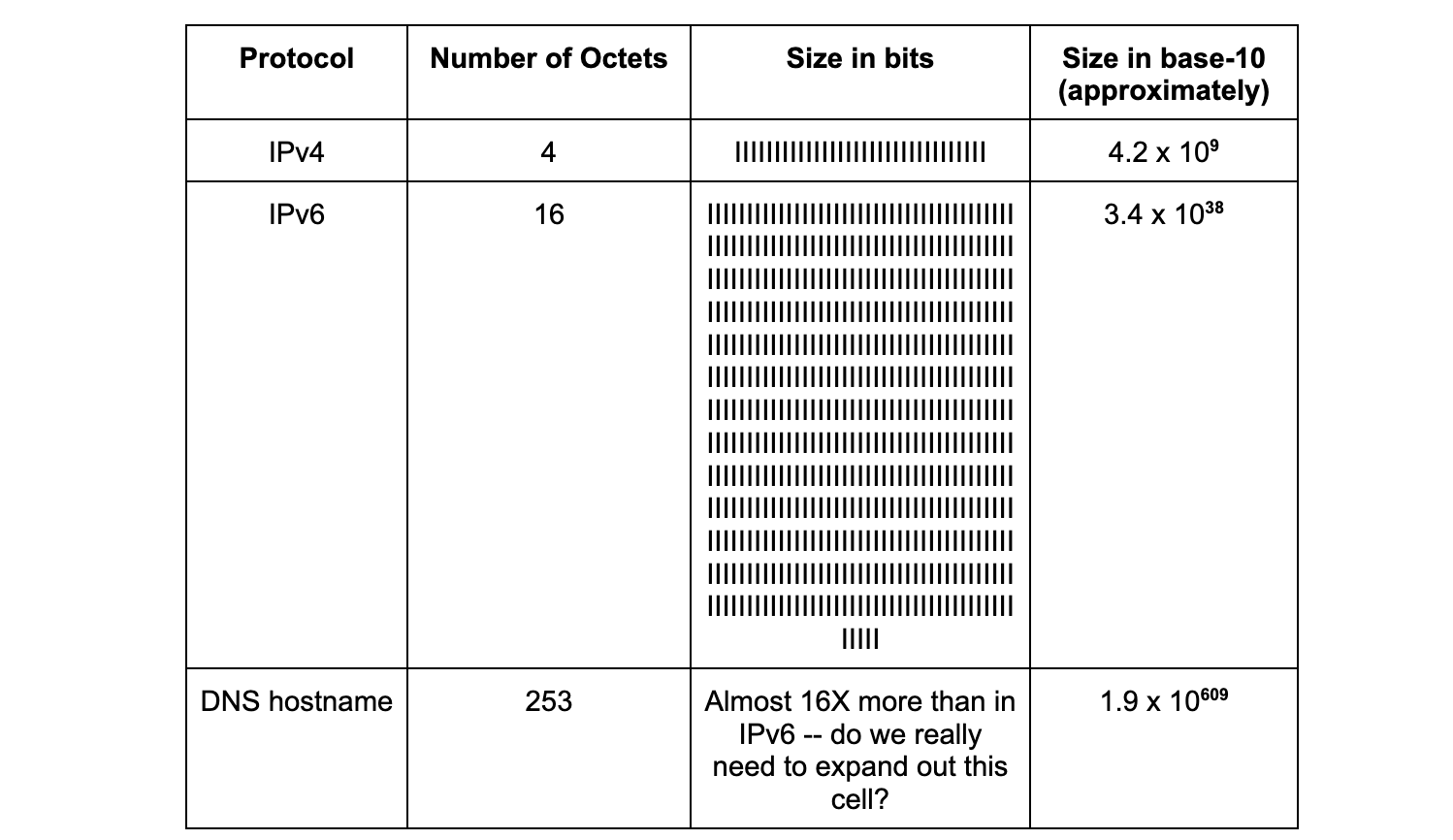

The difference in magnitude between names and addresses is also codified in the specifications. IPv4 addresses are 32 bits, and IPv6 addresses are 128 bits. The size of a domain name that can be queried by DNS is as many as 253 octets, or 2,024 bits (from Section 2.3.4 in RFC 1035, published 1987). The table below helps to put those differences into perspective:

On November 15, 2022, the United Nations announced the population of the Earth surpassed eight billion people. Intuitively, we know that there cannot be anywhere near as many postal addresses. The difference between the number of possible names on the planet, and similarly on the Internet, does and must exceed the number of available addresses.

The proof is in the pudding names!

Now that those two relevant principles about IP addresses and DNS names in the international standards are understood – that IP address and domain names serve distinct purposes and there is no one to one relationship between the two – an examination of a recent case of content blocking using IP addresses can help to see the reasons it is problematic. Take, for example, the IP blocking incident in Austria late August 2022. The goal was to restrict access to 14 target domains, by blocking 11 IP addresses (source: RTR.Telekom. Post via the Internet Archive) — the mismatch between those two numbers should have been a warning flag that IP blocking might not have the desired effect.

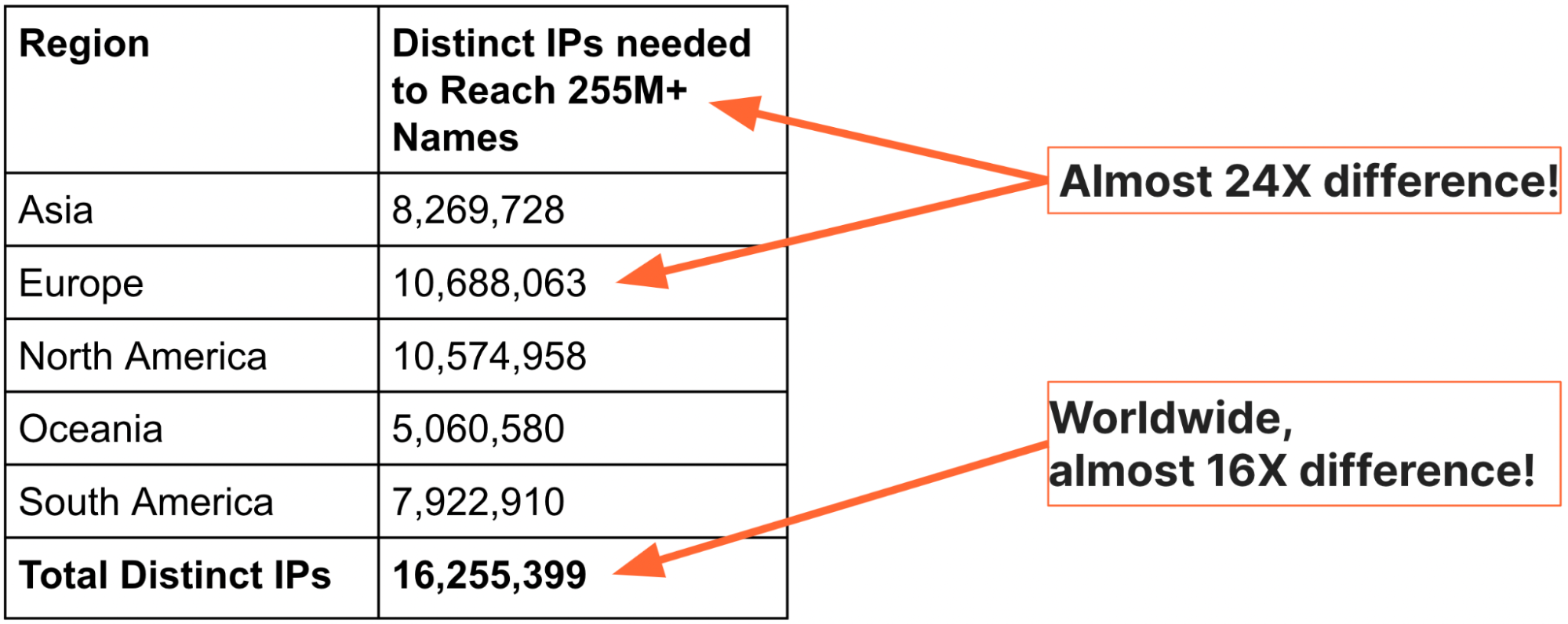

Analogies and international standards may explain the reasons that IP blocking should be avoided, but we can see the scale of the problem by looking at Internet-scale data. To better understand and explain the severity of IP blocking, we decided to generate a global view of domain names and IP addresses (thanks are due to a PhD research intern, Sudheesh Singanamalla, for the effort). In September 2022, we used the authoritative zone files for the top-level domains (TLDs) .com, .net, .info, and .org, together with top-1M website lists, to find a total of 255,315,270 unique names. We then queried DNS from each of five regions and recorded the set of IP addresses returned. The table below summarizes our findings:

The table above makes clear that it takes no more than 10.7 million addresses to reach 255,315,270 million names from any region on the planet, and the total set of IP addresses for those names from everywhere is about 16 million — the ratio of names to IP addresses is nearly 24x in Europe and 16x globally.

There is one more worthwhile detail about the numbers above: The IP addresses are the combined totals of both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses, meaning that far fewer addresses are needed to reach all 255M websites.

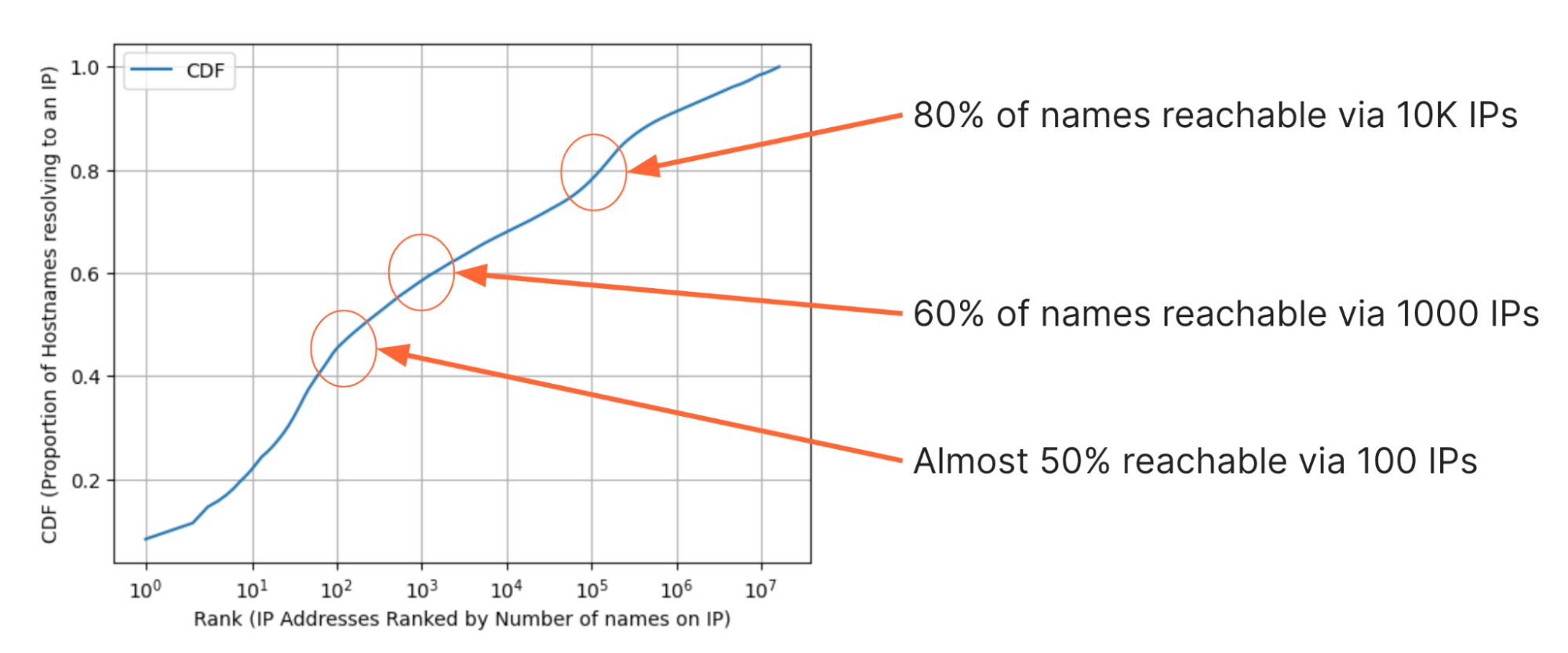

We’ve also inspected the data a few different ways to find some interesting observations. For example, the figure below shows the cumulative distribution (CDF) of the proportion of websites that can be visited with each additional IP address. On the y-axis is the proportion of websites that can be reached given some number of IP addresses. On the x-axis, the 16M IP addresses are ranked from the most domains on the left, to the least domains on the right. Note that any IP address in this set is a response from DNS and so it must have at least one domain name, but the highest numbers of domains on IP addresses in the set number are in the 8-digit millions.

By looking at the CDF there are a few eye-watering observations:

- Fewer than 10 IP addresses are needed to reach 20% of, or approximately 51 million, domains in the set;

- 100 IPs are enough to reach almost 50% of domains;

- 1000 IPs are enough to reach 60% of domains;

- 10,000 IPs are enough to reach 80%, or about 204 million, domains.

In fact, from the total set of 16 million addresses, fewer than half, 7.1M (43.7%), of the addresses in the dataset had one name. On this ‘one’ point we must be additionally clear: we are unable to ascertain if there was only one and no other names on those addresses because there are many more domain names than those contained only in .com, .org, .info., and .net — there might very well be other names on those addresses.

In addition to having a number of domains on a single IP address, any IP address may change over time for any of those domains. Changing IP addresses periodically can be helpful with certain security, performance, and to improve reliability for websites. One common example in use by many operations is load balancing. This means DNS queries may return different IP addresses over time, or in different places, for the same websites. This is a further, and separate, reason why blocking based on IP addresses will not serve its intended purpose over time.

Ultimately, there is no reliable way to know the number of domains on an IP address without inspecting all names in the DNS, from every location on the planet, at every moment in time — an entirely infeasible proposition.

Any action on an IP address must, by the very definitions of the protocols that rule and empower the Internet, be expected to have collateral effects.

Lack of transparency with IP blocking

So if we have to expect that the blocking of an IP address will have collateral effects, and it’s generally agreed that it’s inappropriate or even legally impermissible to overblock by blocking IP addresses that have multiple domains on them, why does it still happen? That’s hard to know for sure, so we can only speculate. Sometimes it reflects a lack of technical understanding about the possible effects, particularly from entities like judges who are not technologists. Sometimes governments just ignore the collateral damage – as they do with Internet shutdowns – because they see the blocking as in their interest. And when there is collateral damage, it’s not usually obvious to the outside world, so there can be very little external pressure to have it addressed.

It’s worth stressing that point. When an IP is blocked, a user just sees a failed connection. They don’t know why the connection failed, or who caused it to fail. On the other side, the server acting on behalf of the website doesn’t even know it’s been blocked until it starts getting complaints about the fact that it is unavailable. There is virtually no transparency or accountability for the overblocking. And it can be challenging, if not impossible, for a website owner to challenge a block or seek redress for being inappropriately blocked.

Some governments, including Austria, do publish active block lists, which is an important step for transparency. But for all the reasons we’ve discussed, publishing an IP address does not reveal all the sites that may have been blocked unintentionally. And it doesn’t give those affected a means to challenge the overblocking. Again, in the physical world example, it’s hard to imagine a court order on a skyscraper that wouldn’t be posted on the door, but we often seem to jump over such due process and notice requirements in virtual space.

We think talking about the problematic consequences of IP blocking is more important than ever as an increasing number of countries push to block content online. Unfortunately, ISPs often use IP blocks to implement those requirements. It may be that the ISP is newer or less robust than larger counterparts, but larger ISPs engage in the practice, too, and understandably so because IP blocking takes the least effort and is readily available in most equipment.

And as more and more domains are included on the same number of IP addresses, the problem is only going to get worse.

Next steps

So what can we do?

We believe the first step is to improve transparency around the use of IP blocking. Although we’re not aware of any comprehensive way to document the collateral damage caused by IP blocking, we believe there are steps we can take to expand awareness of the practice. We are committed to working on new initiatives that highlight those insights, as we’ve done with the Cloudflare Radar Outage Center.

We also recognize that this is a whole Internet problem, and therefore has to be part of a broader effort. The significant likelihood that blocking by IP address will result in restricting access to a whole series of unrelated (and untargeted) domains should make it a non-starter for everyone. That’s why we’re engaging with civil society partners and like-minded companies to lend their voices to challenge the use of blocking IP addresses as a way of addressing content challenges and to point out collateral damage when they see it.

To be clear, to address the challenges of illegal content online, countries need legal mechanisms that enable the removal or restriction of content in a rights-respecting way. We believe that addressing the content at the source is almost always the best and the required first step. Laws like the EU’s new Digital Services Act or the Digital Millennium Copyright Act provide tools that can be used to address illegal content at the source, while respecting important due process principles. Governments should focus on building and applying legal mechanisms in ways that least affect other people’s rights, consistent with human rights expectations.

Very simply, these needs cannot be met by blocking IP addresses.

We’ll continue to look for new ways to talk about network activity and disruption, particularly when it results in unnecessary limitations on access. Check out Cloudflare Radar for more insights about what we see online.