Post Syndicated from Grab Tech original https://engineering.grab.com/trident-real-time-event-processing-at-scale

Ever wondered what goes behind the scenes when you receive advisory messages on a confirmed booking? Or perhaps how you are awarded with rewards or points after completing a GrabPay payment transaction? At Grab, thousands of such campaigns targeting millions of users are operated daily by a backbone service called Trident. In this post, we share how Trident supports Grab’s daily business, the engineering challenges behind it, and how we solved them.

What is Trident?

Trident is essentially Grab’s in-house real-time if this, then that (IFTTT) engine, which automates various types of business workflows. The nature of these workflows could either be to create awareness or to incentivize users to use other Grab services.

If you are an active Grab user, you might have noticed new rewards or messages that appear in your Grab account. Most likely, these originate from a Trident campaign. Here are a few examples of types of campaigns that Trident could support:

- After a user makes a GrabExpress booking, Trident sends the user a message that says something like “Try out GrabMart too”.

- After a user makes multiple ride bookings in a week, Trident sends the user a food reward as a GrabFood incentive.

- After a user is dropped off at his office in the morning, Trident awards the user a ride reward to use on the way back home on the same evening.

- If a GrabMart order delivery takes over an hour of waiting time, Trident awards the user a free-delivery reward as compensation.

- If the driver cancels the booking, then Trident awards points to the user as a compensation.

- With the current COVID pandemic, when a user makes a ride booking, Trident sends a message to both the passenger and driver reminding about COVID protocols.

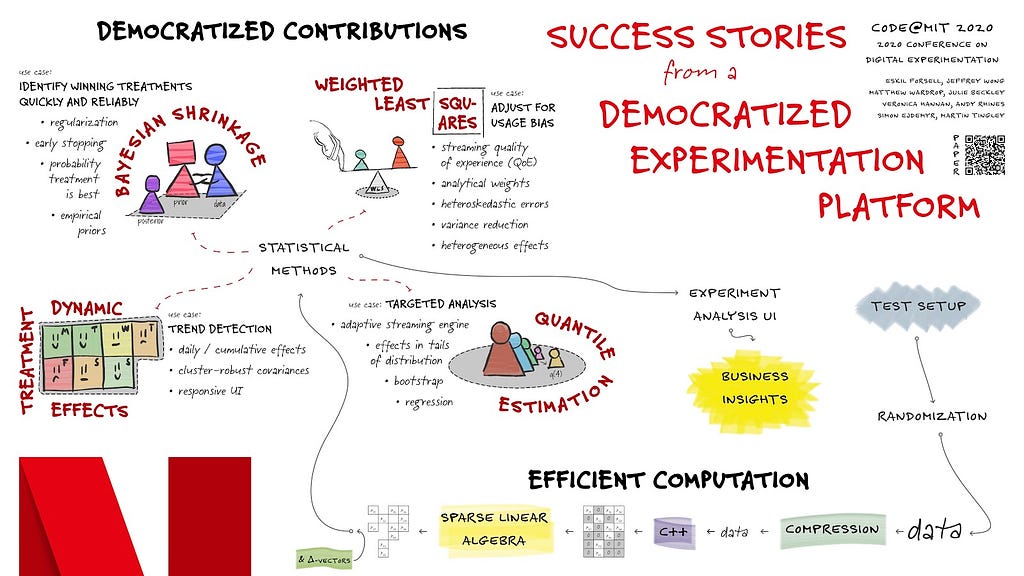

Trident processes events based on campaigns, which are basically a logic configuration on what event should trigger what actions under what conditions. To illustrate this better, let’s take a sample campaign as shown in the image below. This mock campaign setup is taken from the Trident Internal Management portal.

This sample setup basically translates to: for each user, count his/her number of completed GrabMart orders. Once he/she reaches 2 orders, send him/her a message saying “Make one more order to earn a reward”. And if the user reaches 3 orders, award him/her the reward and send a congratulatory message. 😁

Other than the basic event, condition, and action, Trident also allows more fine-grained configurations such as supporting the overall budget of a campaign, adding limitations to avoid over awarding, experimenting A/B testing, delaying of actions, and so on.

An IFTTT engine is nothing new or fancy, but building a high-throughput real-time IFTTT system poses a challenge due to the scale that Grab operates at. We need to handle billions of events and run thousands of campaigns on an average day. The amount of actions triggered by Trident is also massive.

In the month of October 2020, more than 2,000 events were processed every single second during peak hours. Across the entire month, we awarded nearly half a billion rewards, and sent over 2.5 billion communications to our end-users.

Now that we covered the importance of Trident to the business, let’s drill down on how we designed the Trident system to handle events at a massive scale and overcame the performance hurdles with optimization.

Architecture design

We designed the Trident architecture with the following goals in mind:

- Independence: It must run independently of other services, and must not bring performance impacts to other services.

- Robustness: All events must be processed exactly once (i.e. no event missed, no event gets double processed).

- Scalability: It must be able to scale up processing power when the event volume surges and withstand when popular campaigns run.

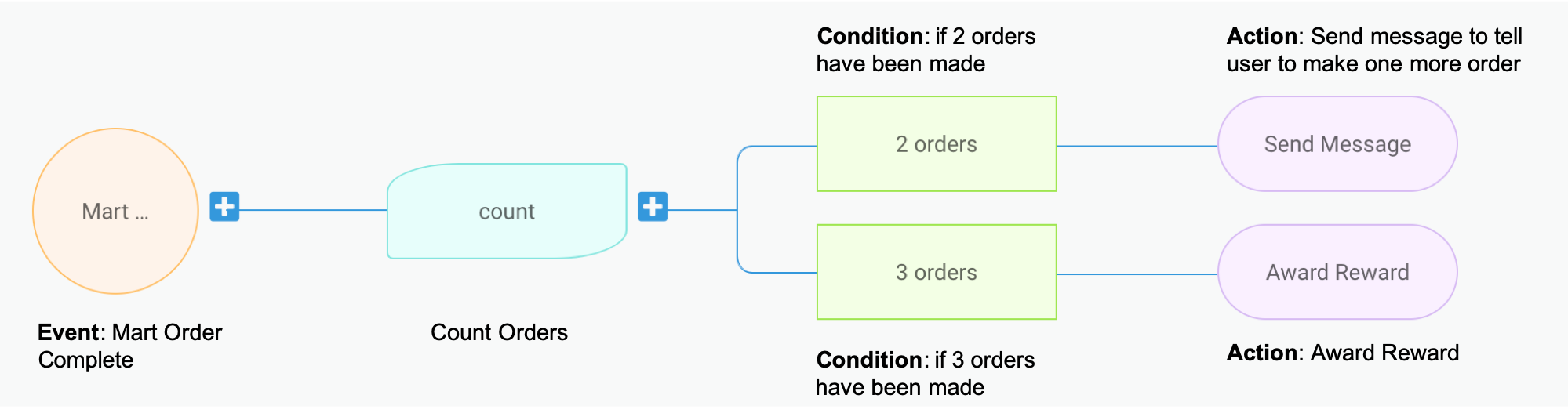

The following diagram depicts how the overall system architecture looks like.

Trident consumes events from multiple Kafka streams published by various backend services across Grab (e.g. GrabFood orders, Transport rides, GrabPay payment processing, GrabAds events). Given the nature of Kafka streams, Trident is completely decoupled from all other upstream services.

Each processed event is given a unique event key and stored in Redis for 24 hours. For any event that triggers an action, its key is persisted in MySQL as well. Before storing records in both Redis and MySQL, we make sure any duplicate event is filtered out. Together with the at-least-once delivery guaranteed by Kafka, we achieve exactly-once event processing.

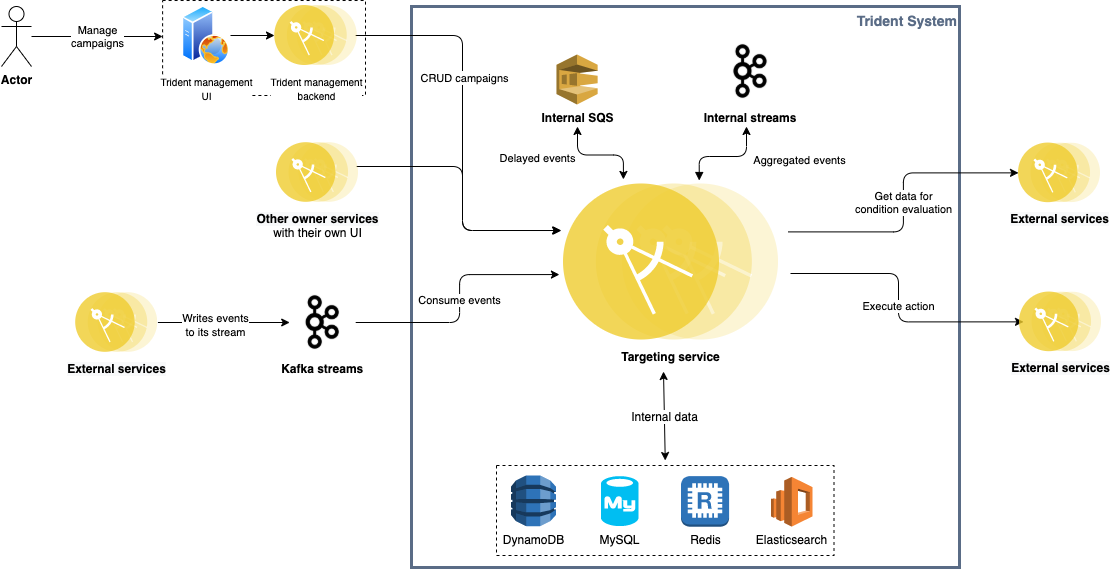

Scalability is a key challenge for Trident. To achieve high performance under massive event volume, we needed to scale on both the server level and data store level. The following mind map shows an outline of our strategies.

Scale servers

Our source of events are Kafka streams. There are mostly two factors that could affect the load on our system:

- Number of events produced in the streams (more rides, food orders, etc. results in more events for us to process).

- Number of campaigns running.

- Nature of campaigns running. The campaigns that trigger actions for more users cause higher load on our system.

There are naturally two types of approaches to scale up server capacity:

- Distribute workload among server instances.

- Reduce load (i.e. reduce the amount of work required to process each event).

Distribute load

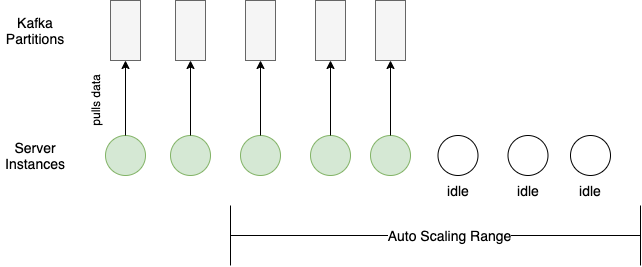

Distributing workload seems trivial with the load balancing and auto-horizontal scaling based on CPU usage that cloud providers offer. However, an additional server sits idle until it can consume from a Kafka partition.

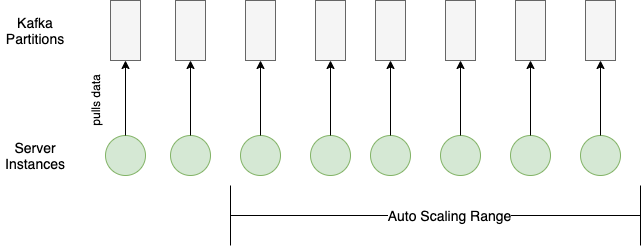

Each Kafka partition can only be consumed by one consumer within the same consumer group (our auto-scaling server group in this case). Therefore, any scaling in or out requires matching the Kafka partition configuration with the server auto-scaling configuration.

Here’s an example of a bad case of load distribution:

And here’s an example of a good load distribution where the configurations for the Kafka partitions and the server auto-scaling match:

Within each server instance, we also tried to increase processing throughput while keeping the resource utilization rate in check. Each Kafka partition consumer has multiple goroutines processing events, and the number of active goroutines is dynamically adjusted according to the event volume from the partition and time of the day (peak/off-peak).

Reduce load

You may ask how we reduced the amount of processing work for each event. First, we needed to see where we spent most of the processing time. After performing some profiling, we identified that the rule evaluation logic was the major time consumer.

What is rule evaluation?

Recall that Trident needs to operate thousands of campaigns daily. Each campaign has a set of rules defined. When Trident receives an event, it needs to check through the rules for all the campaigns to see whether there is any match. This checking process is called rule evaluation.

More specifically, a rule consists of one or more conditions combined by AND/OR Boolean operators. A condition consists of an operator with a left-hand side (LHS) and a right-hand side (RHS). The left-hand side is the name of a variable, and the right-hand side a value. A sample rule in JSON:

Country is Singapore and taxi type is either JustGrab or GrabCar.

{

"operator": "and",

"conditions": [

{

"operator": "eq",

"lhs": "var.country",

"rhs": "sg"

},

{

"operator": "or",

"conditions": [

{

"operator": "eq",

"lhs": "var.taxi",

"rhs": <taxi-type-id-for-justgrab>

},

{

"operator": "eq",

"lhs": "var.taxi",

"rhs": <taxi-type-id-for-grabcard>

}

]

}

]

}

When evaluating the rule, our system loads the values of the LHS variable, evaluates against the RHS value, and returns as result (true/false) whether the rule evaluation passed or not.

To reduce the resources spent on rule evaluation, there are two types of strategies:

- Avoid unnecessary rule evaluation

- Evaluate “cheap” rules first

We implemented these two strategies with event prefiltering and weighted rule evaluation.

Event prefiltering

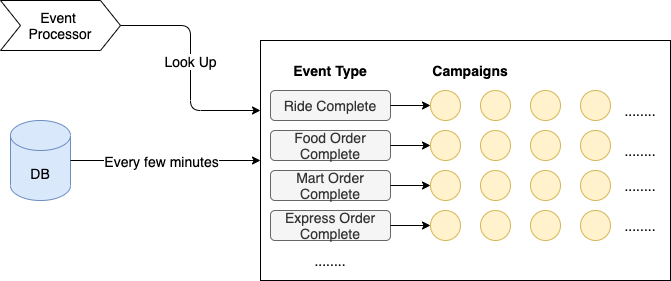

Just like the DB index helps speed up data look-up, having a pre-built map also helped us narrow down the range of campaigns to evaluate. We loaded active campaigns from the DB every few minutes and organized them into an in-memory hash map, with event type as key, and list of corresponding campaigns as the value. The reason we picked event type as the key is that it is very fast to determine (most of the time just a type assertion), and it can distribute events in a reasonably even way.

When processing events, we just looked up the map, and only ran rule evaluation on the campaigns in the matching hash bucket. This saved us at least 90% of the processing time.

Weighted rule evaluation

Evaluating different rules comes with different costs. This is because different variables (i.e. LHS) in the rule can have different sources of values:

- The value is already available in memory (already consumed from the event stream).

- The value is the result of a database query.

- The value is the result of a call to an external service.

These three sources are ranked by cost:

In-memory < database < external service

We aimed to maximally avoid evaluating expensive rules (i.e. those that require calling external service, or querying a DB) while ensuring the correctness of evaluation results.

First optimization – Lazy loading

Lazy loading is a common performance optimization technique, which literally means “don’t do it until it’s necessary”.

Take the following rule as an example:

A & B

If we load the variable values for both A and B before passing to evaluation, then we are unnecessarily loading B if A is false. Since most of the time the rule evaluation fails early (for example, the transaction amount is less than the given minimum amount), there is no point in loading all the data beforehand. So we do lazy loading ie. load data only when evaluating that part of the rule.

Second optimization – Add weight

Let’s take the same example as above, but in a different order.

B & A

Source of data for A is memory and B is external service

Now even if we are doing lazy loading, in this case, we are loading the external data always even though it potentially may fail at the next condition whose data is in memory.

Since most of our campaigns are targeted, a popular condition is to check if a user is in a certain segment, which is usually the first condition that a campaign creator sets. This data resides in another service. So it becomes quite expensive to evaluate this condition first even though the next condition’s data can be already in memory (e.g. if the taxi type is JustGrab).

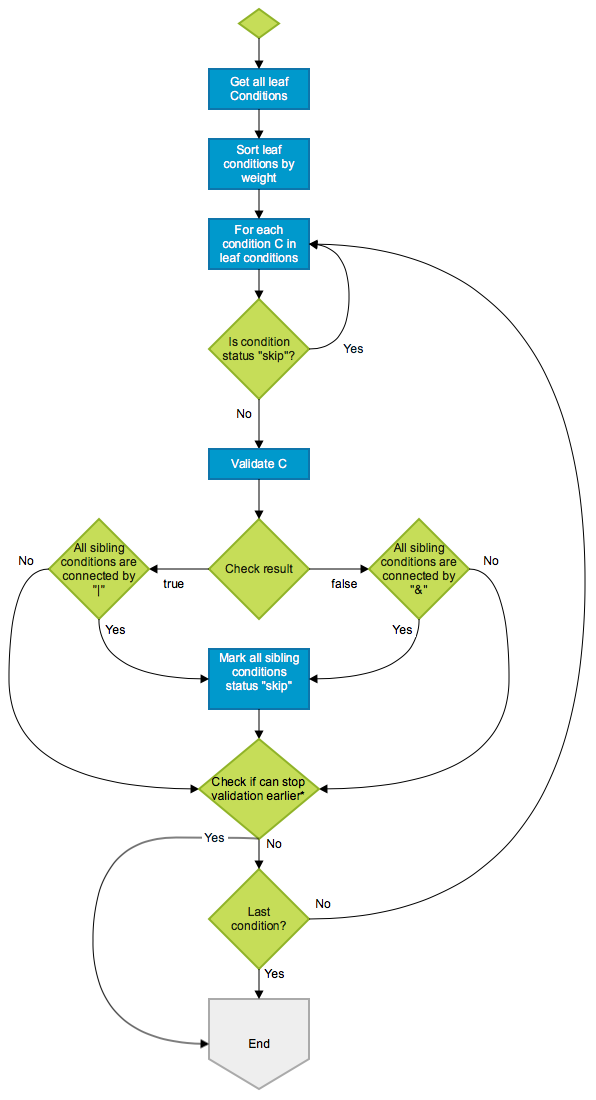

So, we did the next phase of optimization here, by sorting the conditions based on weight of the source of data (low weight if data is in memory, higher if it’s in our database and highest if it’s in an external system). If AND was the only logical operator we supported, then it would have been quite simple. But the presence of OR made it complex. We came up with an algorithm that sorts the evaluation based on weight keeping in mind the AND/OR. Here’s what the flowchart looks like:

An example:

Conditions: A & ( B | C ) & ( D | E )

Actual result: true & ( false | false ) & ( true | true ) --> false

Weight: B < D < E < C < A

Expected check order: B, D, C

Firstly, we start validating B which is false. Apparently, we cannot skip the sibling conditions here since B and C are connected by |. Next, we check D. D is true and its only sibling E is connected by | so we can mark E “skip”. Then, we check E but since E has been marked “skip”, we just skip it. Still, we cannot get the final result yet, so we need to continue validating C which is false. Now we know (B | C) is false so the whole condition is false too. We can stop now.

Sub-streams

After investigation, we learned that we consumed a particular stream that produced terabytes of data per hour. It caused our CPU usage to shoot up by 30%. We found out that we process only a handful of event types from that stream. So we introduced a sub-stream in between, which contains the event types we want to support. This stream is populated from the main stream by another server, thereby reducing the load on Trident.

Protect downstream

While we scaled up our servers wildly, we needed to keep in mind that there were many downstream services that received more traffic. For example, we call the GrabRewards service for awarding rewards or the LocaleService for checking the user’s locale. It is crucial for us to have control over our outbound traffic to avoid causing any stability issues in Grab.

Therefore, we implemented rate limiting. There is a total rate limit configured for calling each downstream service, and the limit varies in different time ranges (e.g. tighter limit for calling critical service during peak hour).

Scale data store

We have two types of storage in Trident: cache storage (Redis) and persistent storage (MySQL and others).

Scaling cache storage is straightforward, since Redis Cluster already offers everything we need:

- High performance: Known to be fast and efficient.

- Scaling capability: New shards can be added at any time to spread out the load.

- Fault tolerance: Data replication makes sure that data does not get lost when any single Redis instance fails, and auto election mechanism makes sure the cluster can always auto restore itself in case of any single instance failure.

All we needed to make sure is that our cache keys can be hashed evenly into different shards.

As for scaling persistent data storage, we tackled it in two ways just like we did for servers:

- Distribute load

- Reduce load (both overall and per query)

Distribute load

There are two levels of load distribution for persistent storage: infra level and DB level. On the infra level, we split data with different access patterns into different types of storage. Then on the DB level, we further distributed read/write load onto different DB instances.

Infra level

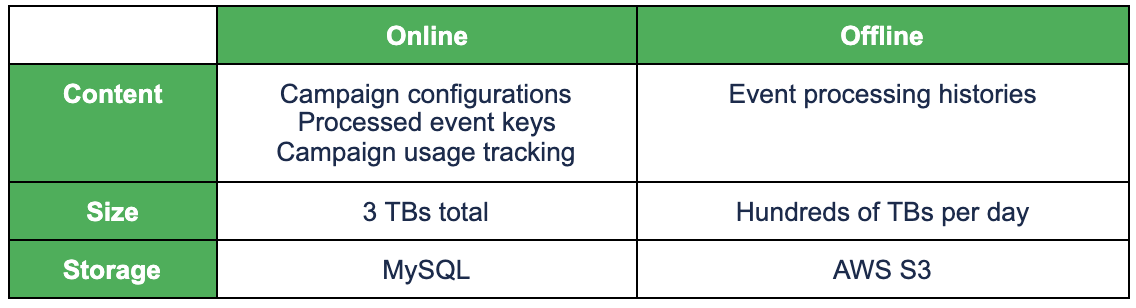

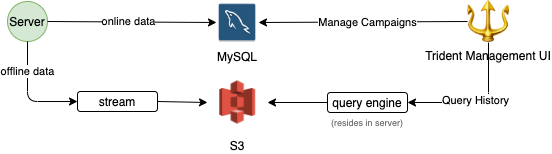

Just like any typical online service, Trident has two types of data in terms of access pattern:

- Online data: Frequent access. Requires quick access. Medium size.

- Offline data: Infrequent access. Tolerates slow access. Large size.

For online data, we need to use a high-performance database, while for offline data, we can just use cheap storage. The following table shows Trident’s online/offline data and the corresponding storage.

Writing of offline data is done asynchronously to minimize performance impact as shown below.

For retrieving data for the users, we have high timeout for such APIs.

DB level

We further distributed load on the MySQL DB level, mainly by introducing replicas, and redirecting all read queries that can tolerate slightly outdated data to the replicas. This relieved more than 30% of the load from the master instance.

Going forward, we plan to segregate the single MySQL database into multiple databases, based on table usage, to further distribute load if necessary.

Reduce load

To reduce the load on the DB, we reduced the overall number of queries and removed unnecessary queries. We also optimized the schema and query, so that query completes faster.

Query reduction

We needed to track usage of a campaign. The tracking is just incrementing the value against a unique key in the MySQL database. For a popular campaign, it’s possible that multiple increment (a write query) queries are made to the database for the same key. If this happens, it can cause an IOPS burst. So we came up with the following algorithm to reduce the number of queries.

- Have a fixed number of threads per instance that can make such a query to the DB.

- The increment queries are queued into above threads.

- If a thread is idle (not busy in querying the database) then proceed to write to the database then itself.

- If the thread is busy, then increment in memory.

- When the thread becomes free, increment by the above sum in the database.

To prevent accidental over awarding of benefits (rewards, points, etc), we require campaign creators to set the limits. However, there are some campaigns that don’t need a limit, so the campaign creators just specify a large number. Such popular campaigns can cause very high QPS to our database. We had a brilliant trick to address this issue- we just don’t track if the number is high. Do you think people really want to limit usage when they set the per user limit to 100,000? 😉

Query optimization

One of our requirements was to track the usage of a campaign – overall as well as per user (and more like daily overall, daily per user, etc). We used the following query for this purpose:

INSERT INTO … ON DUPLICATE KEY UPDATE value = value + inc

The table had a unique key index (combining multiple columns) along with a usual auto-increment integer primary key. We encountered performance issues arising from MySQL gap locks when high write QPS hit this table (i.e. when popular campaigns ran). After testing out a few approaches, we ended up making the following changes to solve the problem:

- Removed the auto-increment integer primary key.

- Converted the secondary unique key to the primary key.

Conclusion

Trident is Grab’s in-house real-time IFTTT engine, which processes events and operates business mechanisms on a massive scale. In this article, we discussed the strategies we implemented to achieve large-scale high-performance event processing. The overall ideas of distributing and reducing load may be straightforward, but there were lots of thoughts and learnings shared in detail. If you have any comments or questions about Trident, feel free to leave a comment below.

All the examples of campaigns given in the article are for demonstration purpose only, they are not real live campaigns.

Join us

Grab is more than just the leading ride-hailing and mobile payments platform in Southeast Asia. We use data and technology to improve everything from transportation to payments and financial services across a region of more than 620 million people. We aspire to unlock the true potential of Southeast Asia and look for like-minded individuals to join us on this ride.

If you share our vision of driving South East Asia forward, apply to join our team today.